Flouncing: July 1834

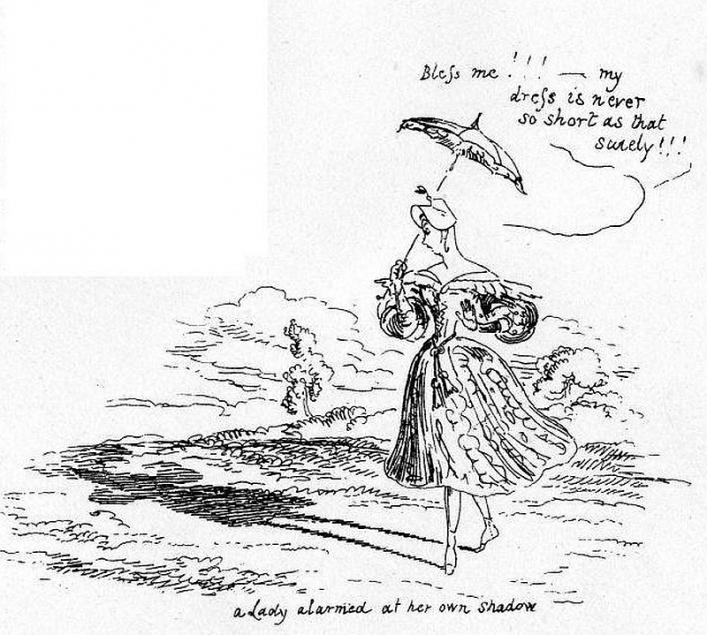

Vive la Flounce! A comic piece in the form of a letter to the Editor of the Star newspaper of July 24, 1834, on the islands' peculiar custom of 'flouncing,' or affiancing, by a visiting wit who called himself 'Time-killer;' and a description of flouncing in Alderney, from Captain Wood's Subaltern Officer, published in 1825. The pictures are from Cruickshank's Sketchbook of 1834-6, part of the Priaulx Library's extensive collection of work by this illustrator.

Flouncing in Guernsey

Flouncing in Alderney

Louisa Lane Clarke, Folk-lore of Guernsey and Sark:

The Guernsey custom in betrothal, or Fiançailles, is that the man gives six silver tea-spoons with the initials of both blended in a monogram and returned if the engagement is decidedly broken off.

SIR—The incognito which I have preserved during the long interval which has elapsed since I last had the pleasure of addressing you, has enabled me to hear many speculations as to the cause of my silence. Some have surmised that TIME-KILLER has departed this life—others, that he had only departed the island—some imagined that he had taken up his abode at Barbet’s Hotel1—whilst others actually apprehended that he had committed—matrimony.

None of these things has yet happened to me; the simple reason of my silence is that I have been 'flounced,' which, being interpreted from the vernacular into plain English, signifieth that I am engaged, caught, or bespoken.

You must know, Mr Editor, that I am a great admirer of a good foot and ankle, and having been informed that some of the ladies who were conscious of possessing this inestimable gift, were frequently in the habit of mounting and descending the Constitution Steps,2 I determined, with due feelings of gratitude, to avail myself of their liberality.

When the gods ordain a man to marry, they first make him drunk. I became intoxicated; a pair of legs fairly ran away with my heart—and it seems decided that the sight of a well-shaped foot is destined to cost me my hand. In plain terms, I fell in love; and feeling my case to be desperate, I boldly made my proposal. I was accepted, and in a short time was given to understand that I must look upon myself as being regularly 'flounced.' I had scarcely time, and indeed it was but little necessary, to inquire the meaning of this term, for the practical illustrations came fast and thick upon me. I was of course invited by my future parents to what they termed a family dinner: the drawing-room furniture denuded of its white coverings was, for the first time in eighteen months, exposed on this solemnity, and, installed in a distinguished place with the 'lovely Thaïs seated by my side,' I was introduced to a most imposing array of aunts, uncles, and cousins. Manifold were the greetings, the compliments, the embracings I had the happiness to undergo; indeed I find, on an enumeration of my new kinsfolk, that I must have kissed or shaken hands with no fewer than sixty-eight—without reckoning the little children. Subsequently I have been the companion of my charmer’s walks, when she has confidingly leant upon my arm—I have escorted her to church, and looked out the places for her in the prayer-book—we have driven tête-à-tête to Alexander’s, where we have feasted upon love and pancakes—and we have visited together the Cave Mahé [Creux Mahie], where my beloved’s dexterity in entering on all fours gave me as much gratification as any other of the natural beauties which the scene presented. Besides, I have been taken through a complete course of tea and currant cake, and have even, on one occasion, been admitted to a 'humdrum.'3

In addition to these privileges of my happy situation, I have been consulted on the affairs of several of the charities of which my beloved is an active member. My opinion has been appealed to in a case of disputed baby-linen. I have likewise been favoured with the perusal of my fair one’s album,4 consisting of three folio volumes. I have even been indulged by her acceptance of a few trifles of my composition, under the titles of 'Farewell', 'Forget-me-not,' 'Meet me by the moonlit shore,' and others of equal novelty: and I have been gratified by the assurance that she thinks I really write 'very prettily.' I have also copied for her a moderate sized volume of music, which she protests is very neatly done; and she flatters me with the hope of frequently permitting me, after marriage, to oblige her in the same manner. In that, Mr Editor, as I before stated, I am a 'flounced' man, and of course, with so many favours, so may privileges to be grateful for, it will be concluded that I am, or ought to be, the happiest of human beings. But alas! What a wayward animal is man!

I apprehend that I am overcome by this exceeding weight of happiness. I am unfortunately rather indolent—and I become tired even with the most agreeable occupations. I am besides a very bashful man, and the prominent part which I have been called upon to act, the broad light into which I seem to have dropt as it were through a trap door, are cruelly embarrassing to me. I am likewise small of stature—but, with an ambition common to men of my inches, I have chosen a partner a good head and shoulders taller than myself, so that when on duty—or, in other words, when I am escorting her on our daily walks—I with my small hat and small person, she with her large gigots and flowing veil—I feel, and I am sure must look very much like a little vessel captured and towed along by a large one. Then again I have been surfeited with tea, and have had indigestion of currant cake. I begin to find it somewhat laborious to pay one’s addresses to a young lady—papa, mamma, and sixty-eight relations all at one time; and even our walks and jaunts, which have hitherto been so agreeable, will I suspect soon pall on our appetites, as I already perceive my small-talk is on the wane, and I have more than once caught myself joining my beloved in a hearty yawn.

Now what I would wish to be informed of by those learned in the law of flouncing, is whether it be not possible to shorten a little the period of probation, or whether some of the prescribed observances cannot be waived or mitigated in favour of an unfortunate stranger. Is there no authority—no female Pope—no conclave of ancient maids and matrons, who, infallible themselves, can grant a dispensation or indulgence to others; or is it rigorously necessary that the flouncing should be accomplished in all its parts? I trust you will do me the service of submitting my case to your experienced readers, and that you or they will favour me by some suggestion by which the burthen of my happiness may be a little lightened. With respect to my fair intended, who, be it observed, is a great stickler for established usages, you will readily believe that I have never ventured to utter a complaint to her—‘tis indeed almost the only liberty I dare not venture on; but I should be extremely glad if I could find any method of letting her know that I would willingly postpone some of my privileges till after marriage, if I could be dispensed from a part of the those observances weigh so heavily on her indolent and bashful little lover.

Excuse the haste with which this is written: the duties of my present situation allow me little time for any other occupation.

Your most obedient servant

TIME-KILLER

July 19th 1834

Captain Wood5 ends his autobiography in Alderney:

With respect to the amiable qualities of the females belonging to the higher classes in this pleasant island, there is reason to say everything complimentary. Alderney may justly be compared to the Island of Calypso; and the attraction of these fair damsels is even more potent than hers, for should any gallant get entangled in the snares of love here, it is almost impossible for him to extricate himself. This no less than five of my brother-officers who were quartered in this fascinating place can testify, having each married one of the fair residents: and which indeed is not to be wondered at; for where young gentlemen experience attention, respect, and friendship, it is very natural that they should, in return, be induced to share their heart, love, and fortune, with such engaging and endearing objects; and were this condescension a little more practised in England, I am opinion that the female part of society would be materially benefitted.

When I remark that it is impossible for a gentleman to extricate himself if he fall in love in this island, I do not mean to infer that he is entangled like a bird in a net; but should he quit the island without marrying the object of his attachment, he is obliged to return and complete his courtship by marriage. This is owing to a strange practice prevalent in these islands which is called flouncing; and when this, which is nothing more than keeping each other company, takes place, it is held as sacred as a marriage contract: thus, if once a gentleman is flounced, or engaged to a lady, she never by any chance thinks of another object of affection, but implicitly relies on her gallant's honour, which is rarely, if ever, forfeited.

Vive la Flounce! may flouncing flourish while there are cows to milk and maidens to marry in Alderney!!

[London Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, 1825.]

1 The prison.

2 A respectable area of St Peter Port.

3 Alexander's (for Monsieur Alexandre, its host) was a popular tavern and eating-place in St Saviour. Membership of social clubs, of which there were many, was a mania in Guernsey from the late 18th century onwards. Humdrums were ladies' clubs, made up of friends and acquaintances of equal status, and very exclusive.

4 The Library has one such album, dating from 1834, which belonged to Jane Chegwin of Guernsey, and which can be viewed on request.

5 Captain George Wood, The Subaltern Officer, London, Prowett, 1825.