Jacques Le Batard

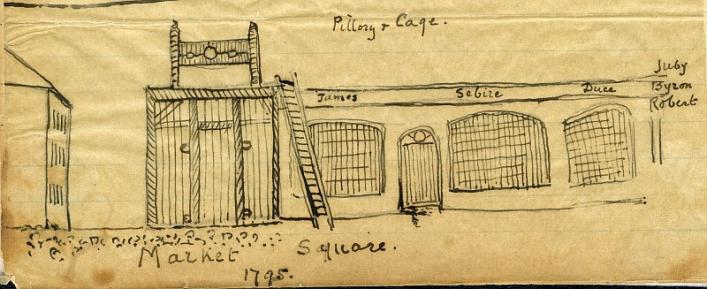

The Gazette de L'Isle de Guernesey, of which the Priaulx Library has copies to view, published an unusual announcement in July of 1795. The newspaper reproduced in its entirety the sentence passed in the Royal Court upon a Frenchman from St Germain in Normandy, called Jacques Le Batard. The results of criminal trials were not normally published in the early Gazettes. Why this one? The sketch of the pillory and cage in 1795 are from the Lukis memoirs in Edith Carey's Scrapbooks in the Library.

Jacques Le Bâtard was found guilty of theft, his crimes apparently going back at least eight years. He generally stole from locked stores and sheds; his modus operandi seems to have included getting through locked doors and leaving them locked behind him. As he allegedly stole 400lb of candle wax at one time and 300 lb of soap, he is presumed to have had accomplices. He was sentenced thus:

And the said Le Bastard, having been proven guilty, is sentenced to 500 Whip lashes, to be delivered on two occasions, thus: 250 lashes of the Whip today, & 250 lashes next Saturday and to have his right ear cut off: all at the hand of the High Executioner. And in addition the said Le Bastard is permanently exiled from this Bailiwick, and is forbidden to return, on pain of being hung by the neck until death: and his goods, property and inheritances, should he have any, are confiscated and become the property of His Majesty or of the seigneur of the fief who has the right to it, after the expenses of the trial are deducted.1

The document was signed by the Greffier, George Le Febvre.

The full account of the sentence in French and English is available.

The punishment seems savage;2 but in Laurent Carey’s exegesis of the laws of Guernsey,3 written in 1769, this is the punishment for theft as given:

DE LARCIN: Pour la première fois le larron est fouetté; pour la seconde, outre le fouet, on lui coupe une oreille, et pour la troisième pendu. Larcin grand et considérable, comme aussi le doméstique, est punissable de mort.

THEFT: upon the first conviction for theft, the thief is to be flogged; for the second, in addition to the flogging, his right ear will be cut off; at the third, he is to be hanged. Serious theft, including theft from the household,4 is punishable by death. The Royal Court would in some cases impose a harsher sentence than a crime warranted if the perpetrator was thought to be of bad character and to have committed other [unproven] offences, a tendency not surprisingly regarded as legally somewhat dubious by contemporary British commentators.5

Jacques Le Bâtard had committed his first recorded crime in Guernsey in 1787. By the time he was brought to court, French exiles from the Revolution were rather unpopular in the islands, their behaviour in public leaving a lot to be desired. He, however, is unlikely to have been a Royalist émigré, having lived here since at least 1787. Although this family name is occasionally found in the island, he was much more likely to have been regarded with distaste as a 'Norman,' i.e. an unsavoury French person who was either a criminal, a spy, or (worse) a beggar, a category of 'Stranger' that the Guernsey authorities had for centuries been trying to cleanse from the island; he is nevertheless recorded as having owned a house at the Corbins in St Peter Port (which was later sold by the States.).6 In those uncertain times, when the jitteriness brought about by a genuine fear of invasion was exacerbated by the many strangers whom the war caused to fetch up in Guernsey, from rough and drunken garrison and foreign soldiers to exiled Frenchmen roaming the island, he may have been made an example of.7

Flogging was nevertheless a common punishment;8 women were flogged as well as men, but only on the shoulders.9 500 lashes, however, was a harsh sentence even in the British navy—although that august body was known to have handed out 1200 lashes at a time. It is, however, unclear with what implement this punishment was administered, the French fouet referring to any sort of whip or lash. In the navy the cat-o’-nine-tails was used; perhaps the Guernsey establishment was less cruel.10 Floggings took place at Le Pilori (Pillory), which was originally to be found next to the present Quay Street (once Rue du Pilori) on the site of the former Woolworths shop. In the eighteenth century the Pillory was moved. F. C. Lukis wrote11 upon the building of the New Market, that

The Mill stream, which ran above the overshot wheel, was conducted beneath a long shed where washerwomen were wont to retire from the public gaze and wash their clothes. This shed continued in the Market Place, where the Pilori was now transported; [built at the NW corner of the vegetable market square, on the end of the long shed which ran parallel with the front & exactly opposite the Rectory House of the Town Parish. [Now Fuzzey’s Auction House, EC 1916]]; beneath this was a barred cage in which culprits, for their misdeeds, were condemned to stand exposed. Against this cage floggings were inflicted – the hands of the offenders being fastened to two rings in the Front of the Cage.

Elsewhere he says that there were four rings on the cage, to which the hands and feet were fastened when flogging was the sentence.

Louis, le pendard, was the executioner. ... The recent changes made in the meat & fish markets necessitated the entire removal of the shed, with the Cage & Pillory as well. The former only is now replaced by an octagonal cage which is transported in a cart or dray to the public market when required.

Elie Brevint in his Notebooks tells us that in July 1650 a new wooden cage was erected in Guernsey's High Street, to replace one destroyed by cannon from Castle Cornet.

A description of these articles can be found in Victor Hugo's Choses Vues. Lukis also remarks anecdotally that:

I saw in 1795 Jacques le Batard, his ear was cut off with a pair of scissors and nailed to the cage, to which he had been tied for his flagellation; my father took me to the post near the pillory when his ear was nailed on it.

This gruesome spectacle prompted someone under the soubriquet Subordination (subordination being 'respect for proper authority,' in Guernsey terms 'know your place')—an unknown enemy of the Bailiff, the controversial and highly irascible William Le Marchant—to submit a ditty to the Gazette of 3 October, 1795:

Le Baillif a mis la Terreur,

Au tonneiller gent cabaleur.

Il tremble pour ses Oreilles,

Qu’il dit sans pareilles.

Mais elles tomberont tôt ou tard,

Comme celle de Le Batard.

Si ce malheur il n’évite,

Par se soumetre au plus vite.'LA SUBORDINATION'

Nous avons suivis la copie lettre à lettre.

Translated, it reads something like this:

The Bailiff has brought Terror

Upon the scoundrel of the Cabal;

He trembles with fear for his Ears

Which he tells us have no peers;

But sooner or later tumble they must,

Just like Le Batard’s bit the dust.

Unless he avoids this awful fate

By giving in before it’s too late.

'SUBORDINATION'

Publisher’s note: We have copied the text letter for letter.

William Le Marchant’s abrasive and domineering style earned him enemies, many of whom met at Rossetti’s Assembly Rooms (now the Guille-Allès Library). Le Marchant referred to this group of worthies as 'The Cabal,' or the 'Coffee-House Junta.' The 'tonneilleur' is translated as scoundrel, assuming that it is a more formal spelling of Guernsey-French tonniaeux. Le Marchant was forced to publish a justification of his behaviour towards the Royal Court in this year, 1795; but this was just one of many similar arguments and publications that had been played out and printed between the Court and the Bailiff over the previous 20 years. One can be sure, however, that the medieval punishment meted out by the Bailiff and the Jurats to Jacques Le Bâtard was remembered for quite some time amongst the good folk of Guernsey.

If you would like to see any of the material upon which this article is based, please contact a Librarian.

1 Et est le dit Le Bastard, après preuve, condamné a recevoir 500 coups de Fouet, en deux fois, savoir; 250 coups de Fouet aujourd’hui, & 250 coups de Fouet samedi prochain & avoir l’oreille droit coupée: - le tout par l’exécuteur de la Haute Justice. Et est en outre le dit Bastard banni perpétuellement hors de ce bailliage, avec défense d’y retourner, à peine d’etre pendu & étranglé jusqu’à ce que mort s’en ensuive: & sont ses biens, meubles & héritages, si aucunes a, confisqués, & acquis à Sa Majesté ou au seigneur de fief a qui droit aura, après les frais du procès pris sur iceux.

² 'Warburton', in his chapter on capital cases (1682) gives a description of the contemporary process of a capital trial (i.e. such felonies as are to be dealt with by the loss of life or limb”); for the later process, see Appendix to Warburton: On the present manner (1822) of dealing with capital cases.

³Essai sur les lois et coûtumes de l’ile de Guernesey par Laurent Carey, Ecr., Juré-Justicier (1765-1769). Publié par ordre de la cour royale de Guernesey: Guernesey: T Bichard, Imprimeur aux États. Rue du bordage, 1889; p. 228.

4 Theft from a household by a servant, though only petit vol, was seen as a serious abuse of trust and was subject to the death penalty in France until the Revolution (a sentence very infrequently imposed, however), and later attracted forced labour or a 5-10 year prison sentence.

5 Warburton, A Treatise on the History, Laws, and Customs of the Island of Guernsey (1682), Guernsey, Dumaresq & Mauger, 1822, p. 127: "But herein it is to be observed, how the court can depart from the law approved, and alter the punishment incident to the crime. If the accusation be for a crime punishable with death, the party accused must suffer that punishment, if he be found guilty; if not guilty, he ought to be acquitted; and the judge, whose office it is, not to make or alter laws, but to put the laws established in execution, ought to proceed accordingly. But if the party, accused of a capital crime, be of evil fame and appear to have committed other offences, not punishable by death, but by other corporal punishment at the discretion of the judge; in such case, the Court may inflict somewhat the more severe punishment, because of the evil character of the man and the vehement suspicion of a higher crime."

6 From the Gazette de L'Isle de Guernesey, 21 June, 1794: Jacques Bastard fait savoir, que sa maison situee à la pompe de Corbin est à louer pour la St Jean prochaine. [Jacques Bastard is letting his house at the Corbins pump from 24 June next.] In the Greffe is an Order of 6th May 1816, in which 'HM officers [are] empowered to sell in rent house, etc., late of Jacques Bastard, etc., sentenced to perpetual banishmnet 11 July 1795.' On beggars, see Ogier, Darryl, Reformation and Society in Guernsey, Suffolk, Boydell Press, 1996, p. 159.

7 Gazette, Sat. 7 December 1791: "T.Q." warns those shopkeepers whose shops front the road that someone attempted the previous week to break in to the premises of M. Levy, silversmith, by jemmying open the wooden shutters with an iron bar; had they been successful they would have got away with a great deal of jewellery and other valuable items: he ends with the words "vu le grand nombre de fraudeurs irlandais & autres qui sont présentement dans l'île - bearing in mind the large number of Irish and other crooks who are in the island at the moment."

8 Edith Carey's Scrapbooks, Vol I, p. 65, Chepmell MSS: "In Guernsey there was no local newspaper, & small as the island is, there were many people at St Peter’s or Torteval who lived & died without seeing the Town. Even in the Vale, as late as 1825, when my father wanted to send Pierre Bichard, a labourer whom he employed, to fetch something from Town, the man, who was past 40, told him he did not even know the way. So delighted was he with his journey, that he afterwards went to Town once a year. The distance was three miles. The old Miss Le Marchant of the Grands Maisons once told me, that one of these High Parish rectors knew so little of what was going on that, on seeing an acquaintance pass his door who had lately been imprisoned and flogged, he innocently asked him, ”Quai nouvelles Vàïsin Jain?”; “On fouitte coum le guiâblle en Ville” was le Vàïsin Jain’s feeling answer. [“Any news, Neighbour Jean?” “They beat you like the devil in Town.”]"

A letter from 'U.L.' in The Star of March 23, 1893, protesting at a recent increase in the use of the lash, says: 'I go back in memory 60 or 70 years, when it was not an uncommon thing on a Saturday afternoon to see a procession coming down High Street on its way to the market, the wretched culprit stripped naked to the waist, surrounded by Halbardiers (pike men), followed by the Sheriff who had to see the sentence duly carried out which was generally 50 or 100 lashes, one or other being usually the dose.' records Elizabeth Tostevin having received 50 lashes for theft in 1803.

10 The Star of February 16th, 1861, reported on the punishment of 50 lashes meted out to Thomas Torode which took place in the prison at the hands of a retired army drummer; Torode 'endured his punishment without flinching, and afterwards declared himslef to be quite ready for his dinner, his appetite not having been at all affected by the operation, which, although vigorously performed, produced no laceration, as the cat used had no knots in it.'

11 F.C. Lukis MS, in Edith Carey, Scrapbooks, I, pp. 61 and 66.