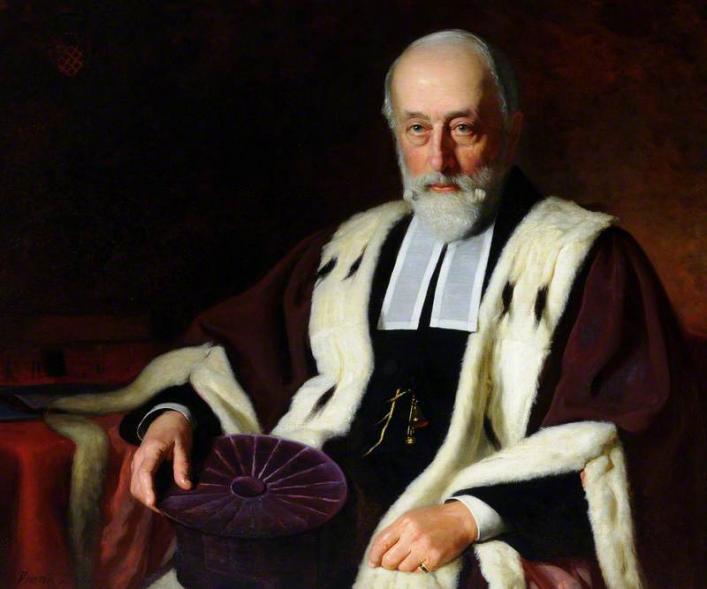

Victor Hugo and Guernsey: Edgar MacCulloch

25th September 2017

Part of the Victor Hugo and Guernsey project. The portrait of Edgar MacCulloch is courtesy of Candie Museum, Guernsey.

Edgar MacCulloch (1808-1896) was a member of a family with strong academic leanings; his uncle was Dr John MacCulloch, FRS, a polymath, specialising in geology, an eminent medical doctor, and great friend of Sir Walter Scott. Edgar was elected jurat in 1844, and in 1850 became president of the Mechanics’ Institution; he was appointed States Supervisor and oversaw the foundation of the New Harbour. In 1869, as Lieutenant-Bailiff, he persuaded the States to save the Chapel of St Apolline. He was the first President of the Guernsey Society of Natural Science (now the Société Guernesiaise.) He was Bailiff from 1884 until 1895. A keen and eminent antiquarian and member of the Folklore Society, he was knighted in 1886.

MacCulloch was a friend of George Métivier, who wrote a poem about him, and both of them could be waspish in their reception of works by the Hugo family. MacCulloch published several articles criticising Les Travailleurs de la mer. He seems to have disliked Hugo, and, obviously determined to take all aspects of the book literally, was very unhappy with the antiquarian and folklore aspects of it:

Considering that the talented author’s residence in Guernsey extended over ten years, it is surprising how little he seems to know of the manners, customs, and mode of thought of the people among whom he dwelt. The specimens of the local dialect which he pretends to give here and there in his novel are almost as unintelligible to a native as if they were written in the Langue d’Oc.

However, Dr Edward Kinnersely Corbin, in notes taken by Louis Aguettant in 1902,¹ makes these remarks:

Hugo, in the Toilers of the Sea, reproduces the Guernsey patois pretty correctly, but not the legends or customs &c of the islands. The descriptions of places are made up.

The local historian Edith Carey edited his collection of Guernsey customs, fairytales, and stories, recorded by him 'at various times' before 1874, and published them in 1903 as Guernsey Folk Lore. In 1864 the author had prepared a preface, eventually published with the book, in which he describes

A desire to preserve, before they were entirely forgotten, some of the traditional stories, and other matters connected with the folk-lore of my native island, induced me to attempt to collect and record them, but I have found the task, though pleasant, by no means easy. The last fifty years has made an immense difference here as elsewhere. The influx of a stranger population, and with it the growth and spread of the English tongue, has changed, or modified considerably, the manners and ideas of the people, more particularly in the town. Old customs are forgotten by the rising generation, what amused their fathers and mothers possesses little or no interest for their children, and gradually even the recollection of these matters dies away ...

His sources included an old family servant, Rachel du Port, and 'my ladies', ladies of leisure who collected material where they could; Edith Carey filled several volumes with her own research on the subject and from this added her own substantial appendix to MacCulloch’s work, including more ghost stories, charms and spells, mostly from her own parish of St Martin's, and poems and ballads in French.

¹ L'Echo Hugo, 2005, pp. 116-117.