My little brothers: Christmas with Victor Hugo, 1862

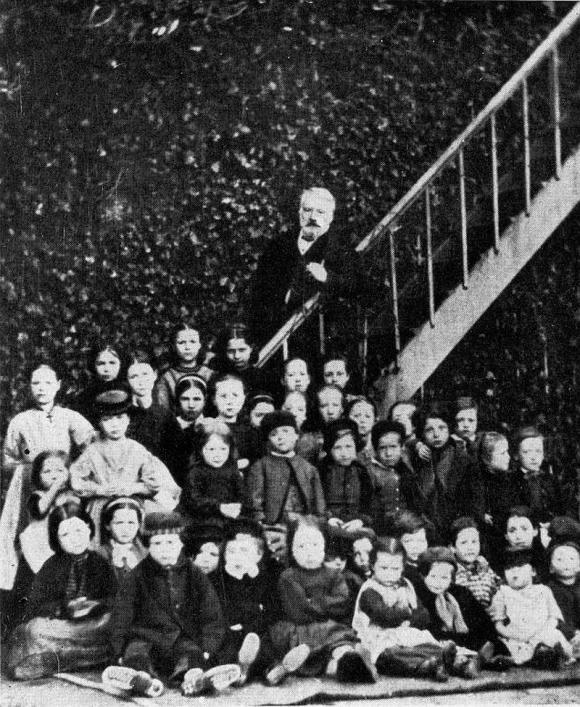

From the Gazette de Guernesey, Saturday 27 December, a report on Hugo's Christmas party for deprived children; a letter from Hugo to his wife, whose idea it all was in the first place; and another to the French publisher Castel, in which he plans to donate the proceeds of a new book of drawings to his poor Guernsey protégés. The editor of the Gazette at this time was Hugo's friend and disciple, Guernseyman Henri Marquand. The photograph accompanying this article is dated 1868. It was taken in March by Arsène Garnier. (Another very similar set of photographs was taken by a Jerseyman with a studio in London, named Henry Frankland, in February 1868; the Library has a photographic plate of one of these iconic images.) This particular photograph was popular with the public at the time; they could buy it in the local shops.

Article by Dinah Bott.

In 1860, Madame Hugo saw a malnourished five-year old in the Guernsey market-place, crying with the pain of having to carry a baby in her arms. The author's wife was moved by this to write to the local newspapers asking for donations to help start up a crèche, or nursery system for deprived children, as was already instituted in France. She organized a bazaar at the Assembly Rooms to raise funds, with help from influential French friends, but could only manage 2,000 francs, not enough. She handed the sum over to the Prévôt to be used for charitable causes.

By 1862 the means of helping the needy children of Guernsey had crystallised as the Oeuvre des enfants pauvres, now seemingly Victor Hugo's project. A French medical report had had a great influence on Hugo; it claimed that just one good meal of meat and a glass of wine a month would transform the health of the French population, children especially. Hugo fed the Guernsey children once a week.

Delalande gives the date of the above photograph, which was taken by Arsène Garnier, as 1868, by which time the children numbered forty. Hugo had given this photograph to his baby grandson Georges as a birthday gift in 1868, and it was framed with a portrait of the baby himself. Hugo wrote a dedication: I send my sweet Georges the portraits of his forty little brothers and sisters in the Good Lord: Victor Hugo, Hauteville House, 21 March 1868. Little Georges, who was the son of Charles Hugo, died a month later in Brussels of meningitis, on 26 April.

A photograph of the very first dinner can be seen at the very bottom of this page of an online guide to Hauteville House; the dinners eventually settled into the pattern of taking place every Monday. Exilium vita est, a book produced by the Paris Musées for Hauteville House for an exhibition in 2002, has a photograph of Hugo and around fifty children (No. 62) and a hand-written list by Julie Chenay, Madame Hugo's sister, of the twenty-five girls who attended the Christmas party in 1866 and the item of clothing they were given (No. 60); a dress, boots, a flannel skirt or apron. Louise Brache, aged 10, received boots; Rachel Herivel, 13, a dress; Clémence Philippe, 10, a dress; Virginie Etasse, 9, a dress, for example. Hugo's speech at the children's Christmas dinners of 1868 and 1869, the year before his exile ended, was reproduced in the local and national newspapers and can be found in Pendant l'exil, 1868, V, and 1869, VIII; in them he celebrates the extension of his bien peu de chose, his 'insignificant thing' around the world.

The Société française de Bienfaisance de Guernesey took up this idea in 1889 and began to provide free school dinners, with the help of local nuns, to around 250 children who attended the island's French schools. See Delalande, Victor Hugo à Hauteville House, p. 60; The Star, November 29 1916 ('Every day from 85 to 95 children receive soup at the school in Burnt Lane'). André Maurois tells us in his famous biography of Hugo that by the time the donations to the poor of Guernsey were in full swing, a third of Hugo's household expenses were taken up by charity: Victor Hugo, Jonathan Cape, 1956, p. 393. Paul Chenay, Hugo's brother-in-law (whom Hugo disliked), asserted in his reminiscences (1902) of his infrequent stays at Hauteville House that Hugo resented the cost of the meals and took very little part in them, just lurking about in the background, a claim dismissed in most reasonable terms by another less partisan witness, Paul Stapfer, in his memoirs of his three years in Guernsey, Victor Hugo à Guernesey: Souvenirs personnels, 1905.

CHRISTMAS TREE

Like all the other newspapers, we have previously reported that once a week M. Victor Hugo gives a large number of poor children an excellent dinner. This great apostle of humanity has just added to his good works. Not content with just feeding the body, he decided that it should be clothed, too, and that these unfortunate children have just as much right to the joys of childhood as their richer counterparts. Thus he has just given out to his thirty-two protégés the clothes they needed, and gave them the pleasure of a Christmas tree,1 decorated with presents suitable for their age. This family get-together took place on Wednesday [Christmas Eve] and was attended by several volunteers. Before handing out the clothes and toys, the poet gave the children a little speech couched in terms they could understand. He told them that it is every man’s duty to give their less well-off brothers some of what they have; that he was happy to do what he was doing for them; but that they should understand that they did not owe him anything, but should be grateful to the Father of all, and if they wanted to thank anyone it should not be him, but God, who makes all things well. He then spoke to them about the enormous importance of work, which is for everyone, depending upon their vocation and abilities. He said that work was the only means of making people happy, virtuous, and good. Finally, he added:

My dear children, amongst the toys I have just given you, you will find no guns, no cannon or swords, no murderous weapon that would make you think of war or destruction. War is a dreadful thing; the people of the world are made for loving one another, not killing each other. The girls will find dolls to play with, ideal for learning how to be mother, which will be their job later in life. For the boys there are little boats and little trains, in other words toys designed to encourage work, progress and the mind, and not destruction.

The toys were then handed out to the children. It was lovely to see the joy on everyone’s faces, and it would be difficult to say who was happier, those who gave the presents, or those who received them. [From the French. DAB]

22 March, 1862, from Victor Hugo in Guernsey to Mme Hugo in Paris:

True socialism unites practicality and theory, and feeds the body with bread at the same time as feeding the soul with ideas .... I called the poor children to my table and I said to them the other morning: 'You are my little brothers—vous êtes mes petits frères.' At the same time I am preaching the great humanitarian idea to people .... Following my orders, dinner begins with these words, recited by the eldest child: 'My Lord, be blessed' and finishes thus: 'My Lord, be thanked'. I believe in God, and I try and get the little ones to believe, and older folk too .... My profession of faith is implicit in the first ten lines of the preface to Les Misérables. No more ignorance or poverty, and while we are waiting for that let us share our bread with the little barefoot children .... Alms have to be hidden, but not brotherhood. Brotherhood needs to set an example. It is scientifically proven that children eating meat just once a month are protected from scrofula, rickets, bone disease, tuberculosis and diptheria: I give them meat twice a month and so keep 24 children healthy. Finally, one last word: I don't mind if people say: Victor Hugo's door in exile is half-open to rich people, and completely open to the poor. [Delalande, Victor Hugo à Hauteville House, 1947. DAB]

Gazette de Guernesey, Saturday 20th December 1862

GOOD WORKS

A few months ago the island’s newspapers reported that Monsieur Victor Hugo, touched by the poverty of some local families, and aware of how important for children’s health is a good diet, had decided to invite a number of poor children to his home to give them a good dinner and glass of Bordeaux. There were ten at first, but the number increased to fifteen and now stands at thirty-two. The following letter appeared in the Journal de Bruges is in connection with this act of charity:

Hauteville-House, 5 October.

My dear Monsieur Castel,

Pure chance led you to see a few of my sketches and doodles, made when I was pretty much day-dreaming, in the margins or cover pages of my manuscripts, drawn just with the ink I had left in my pen. You would like to publish them,2 and that excellent artist M. Paul Chenay is offering to engrave them. You are requesting my agreement to this. However talented Monsieur Chenay may be, I fear that these pen strokes and lines, clumsily put down on paper by a man who was really otherwise engaged at the time, will not look anything like proper drawings, once one starts to make pretensions for them to that status. But you are insistent, and I say yes. My agreement to something really rather ridiculous needs some explanation: so here are my reasons.

Some time ago now I started up a little institution of brotherhood-in-practice in my house in Guernsey, which I want to expand and above all establish more branches of elsewhere. It is not a big thing, so I can talk about it here; it is a weekly meal for needy children. Every week, poor mothers do me the honour of bringing their children to dinner at my house. I started off with eight, then fifteen; now I have thirty-two. The children eat together, all as one, Catholics, Protestants, English, French, Irish, whatever religion or nationality they may be. I invite them to be happy and to laugh and I say to them: Be free. They begin and end the meal with a simple thanks to God, free of all connotations of organised religion and thus potentially more meaningful. My wife, my daughter, my sister-in-law, my son, and my servants and myself wait on them. They eat meat and drink wine, both necessities in maintaining children's health. Afterwards they play, then go to school. Visitors come now and then to witness this humble supper, Catholic priests and Protestant ministers mingling with free-thinking liberals and proscribed democrats, and I don’t think any leave unhappy. I could say more, but I think I have said enough to enable you to understand that this idea of introducing poor families into better-off families’ homes, on a level and at ease with each other, when promulgated by better men than me, and by the kind hearts of women in particular, can’t be a bad thing; I think it is of practical value and potentially a very fruitful enterprise, and that is why I am talking about it here, so that others who want to and can do may follow my example. This is not charity, it is brotherhood. When a poor family enters into the world of a better-off family, it profits us both; it sows the seed of solidarity; it starts up, as it were, the sacred democratic mantra, and encourages it on ahead of us—liberté, égalité, fraternité. It is communion with our less fortunate brothers. We learn to serve them and they learn to like us.

It is with this little project in mind, monsieur, that I think I can swallow my pride and authorise the publication that you propose. The income from this book will go towards the expenses of my needy children. It’s winter; I am quite happy to give clothes to people in rags or shoes to people whose feet are bare. Your book will help me do that. That absolves me from any shame in agreeing to it. I honestly could never have imagined that my drawings, if you really want to dignify them as that, could ever have attracted the attention of a connoisseur like you, and an artist of as rare a talent as Monsieur Paul Chenay; you shall have your wish; my drawings will have to manage as best they can, exposed to the light of day in a way they were never intended to; the critics can have a field day, and I tremble for them; I will leave them to face it alone, but I am sure that my dear poor children will find them excellent.

So go ahead and publish the drawings, Monsieur Castel, and you have both my best wishes for your future success and my kindest regards. VICTOR HUGO. [From the French. DAB]

In 1870, L H Toulzanne published a book, Une semaine à Guernesey (Paris, E Dentu), in which he describes a trip to Guernsey to visit Victor Hugo and take a look around the island that had inspired Les Travailleurs de la mer. Hugo receives him on five separate occasions. Toulzanne has this to say about the children's dinners:

Mme Hugo's death did not make orphans of the Guernsey's poor children: they still had a father—the celebrated poet. He enveloped them in kindness and concern for their welfare, and the care he took of them was touching. Newspapers have reproduced the speech he made on 25 December 1868 at the 'poor childrens' dinner.' Some writers have insinuated that he himself had originally no intention of arranging such a gathering; others have gone further and claimed exactly that. This is most definitely wrong, and in all likelihood just the mischief-making of detractors. Every Monday, Victor Hugo gathers together the poor children around a heavily-laden table: one week the little Guernsey children, the next the little French ones. I was present at one of these dinners, and I found observing it both touching and charming, and really moving. It was the turn of the little French children, and I was pleased to discover that the little diners sparkled with Parisian mischief and childish fun, and that one of them would even have made a good Gavroche.

In their childish naivety these children only saw the good and paternal side of Victor Hugo. Later they would understand, and they would humbly acknowledge their gratitude and admiration; now, they can only see him as the benefactor they love. Nevertheless, even they have been struck by the poet's aura of greatness and majesty: for they call him in their quaint way 'The great Monsieur of Hauteville House.' [DAB]

See also Victor Hugo's Christmas fête, 1865.

1 See Stapfer, Souvenirs Personnels, 1905, pp. 54 ff., and his account of the 1867 Christmas tree for the Guernsey Gazette, in Actes et Paroles, II, p. 241. For an eyewitness account of the 1868 dinner, see Stevens, P., 'The Parson's Tale,' in Report & Trans. Soc. Guern. 1986, pp. 114-115; the Reverend Michael Blagg, a visitor to the island, attends the dinner and hears Hugo's speech; he thinks Hugo's desire to be both slave and servant 'a little like claptrap,' and although he declared Hugo to be 'a Radical in politics and I fear an infidel in Religion,' his dinners for the poor were 'deserving of all praise.'

2 This book of drawings was published in 1863, and is known as the Album Castel. Despite Hugo's optimistic plans for the publication, it went very wrong for him, and so disappointed was he with the book and his brother-in-law Paul Chenay's dishonesty that he refused to have any of his works illustrated again, until the edition of Les Travailleurs de la Mer engraved by Méaulle, original lithographs from which we have available to view in the Library. For more about the Album Castel, see Victor Hugo, Paris: 2003, by Pierre Dassau and Henri Focillon, pp. 69 ff. Chenay's view on the matter is expressed in his rather ill-natured memoir of the period, Victor Hugo à Guernesey, 1902, in which Chenay claims that the book had been Hugo's suggestion all along, and that Hugo had first intended the royalties to be paid to two literary societies that had succumbed to pressure and expelled him, in order to curry favour with them. He quotes a letter from Auguste Vacquerie, one of Hugo's confidants, to Hugo's wife to just this effect, but leaves it undated. He claimed that Hugo's unreasonable demands on the publisher for money had meant that the Album Castel was too expensive and thus had not sold in anything like the numbers that could have been expected. This may be the case, but it took three years or so for the book to be published, and Hugo had undoubtedly thought better of his original intentions. These books are available in the Library.