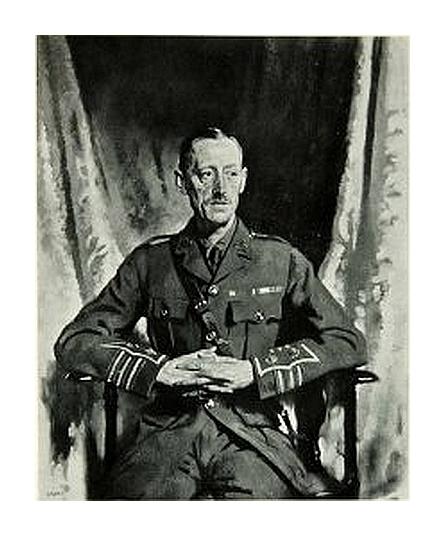

Lieutenant-Colonel Elkington and the retreat from Mons, 1916

'How an Old Elizabethan made good: the stirring story of Lieutenant-Colonel Elkington.' The Star's take on a notorious incident, published in September 1916.

Cashiered very publicly in September 1914, at the very beginning of the First World War,1 and then rehabilitated in spectacular fashion with a Croix de Guerre, John Ford Elkington (1866-1944) was the son of a Guernsey Lieutenant-Governor. Educated at Elizabeth College in Guernsey, he went on to a successful though uneventful career in the army. During the dreadful retreat from Mons, however, on the 27th August 1914, he, as commanding officer of the 1st Royal Warwickshire Regiment, and his sick colleague, Colonel Mainwaring of the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers, somehow agreed in writing with the mayor of St Quentin not to resist the approaching German army. This was in order both to avoid casualties in the small Belgian town and in return for food for his troops, who were utterly exhausted. Mainwaring, who was never reinstated, is thought to have signed the paper, while Elkington made for the train station just outside the town, either to fight the Germans there, or to escape to Paris. The intentions and reasoning behind his actions that day remain controversial, as no transcript of his Court Martial exists. A junior officer under him in the Warwickshires that day was the eventual Field Marshal Montgomery; he cannot have thought too badly of his Colonel, as he unveiled plaques and memorials to Elkington, Elkington's son, and his son-in-law, both casualties of the Second War, in 1946. This is how The Star reacted to Elkington's reinstatement in 1916:

Rank regained by brave actions.

When War broke out, says the Daily Telegraph, among the first troops to cross the Channel for service in France was the 1st battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel John Ford Elkington, whose father was a General. Elkington's professional reputation stood high; he had served throughout the Boer War, gaining the Queen's medal with four clasps. He was popular alike with officers and men, and, what is more, with civilians. During the early weeks of the campaign in France he acquitted himself well. Then, in October, there appeared in the London Gazette the announcement that he had been 'cashiered by sentence of a general court martial.' The charge, let it be added, did not affect his personal courage. A momentary indecision, an error, and he passed out of the Army, apparently a broken man, at an age when it seemed impossible that he could repair his fortunes. His fate excited the sympathy of all who knew him—a brave gentleman who had given his country good, if inconspicuous, service.

What followed constitutes a story that excuses and justifies the resurrection of an incident which in other circumstances it would be the grossest bad taste to refer. Colonel Elkington, already over 50 years of age, enlisted as a ranker in the famous French Foreign Legion. He found himself once more on the battlefields of France, and there it is reported that his conduct was so conspicuous that it was brought to the notice of Colonel Joffre; he had acted in an emergency with extreme bravery. The Médaille Militaire and Croix de Guerre with palm were conferred on this British ex-officer.

In view of these facts it is not surprising that the King has, by order on the Gazette, restored Colonel Elkington to his old rank in the British Army. The story of Elkington's disgrace is pretty well known in its main features to many people. Whether through mistaken humanitarian motives or through a mistakenly exaggerated estimate of the very real fatigue of their troops, the Colonel and another officer made a mistake. Its effects were mitigated by an initiative of others. The thing took place in those awful early days of the war, when the strongest judgment might be bewildered.

Colonel Elkington has proved, in a splendidly practical way, that his fault was at least not want of courage, and in that degree his reinstatement is something more than a personal vindication. It is a satisfaction also to Colonel Elkington's countrymen.

There are elements in this dramatic story which will appeal to the British race throughout the world. It is one of the outstanding romances of the war. The wheel of fortune, influenced by a brave man's dogged courage, has turned full circle. Though this gallant officer, wearing the most cherished decoration a soldier can win under the French colours, may never again see active service, for he was seriously wounded and lay many months in a French hospital, his splendid record will abide. It bears testimony alike to his character and to the traditions of the British Army.

Lieutenant-Colonel Elkington is an Old Elizabethan, and the eldest son of the late Major-General Elkington, CB, who was Lieut.-Governor of Guernsey from 1885 to his death in 1889. He was buried in Cobo cemetery with full military honours.

1 The Library has acquired a book on this incident, by Peter Scott, Dishonoured, the colonels' surrender at St Quentin, published in 1994.

Also a pupil of Elizabeth College, and in the Royal Warwicks with Elkington and Montgomery before the war, was the future Air Commodore Henry Le Marchant Brock, BC, DSO, one of the first founders of the Guernsey Society (see Quarterly Review Guern. Soc. XX (1) 1964 pp. 3 ff.). Born in 1889, he transferred just before the outbreak of the First War from the Warwicks to the Royal Flying Corps, so avoiding this disgrace; he was awarded a DSO and was mentioned in dispatches no fewer than five times. His pamphlet, A record of the birds of Guernsey, was published in 1950 and copies are held in the Library. He died in 1964 and his obituary is to be found in The Quarterly Review of the Guernsey Society XX (2) 1964, p. 40.