Dame Drillot

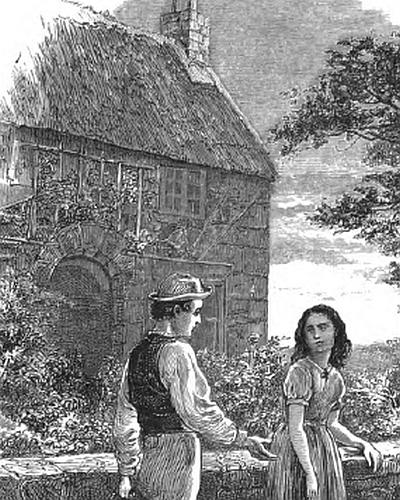

Mary, shown in the illustration in front of the Drillot's farmhouse, meets her future grandmother-in-law, a Guernsey farmer's widow, Marion Drillot; Marion's costume is described in detail. By Frances Carey Brock, from her moralistic but entertaining novel, Clear shining after rain: a Guernsey story, in the Library collection, published in 1871.

Was this the reason why that evening, when she took her first solitary walk, she instinctively found her way to the cottage with the Norman arch, anxious to find out all she could concerning the place and its inmates? In outward appearance, at all events, it was very superior to her uncle's abode, except that it commanded no view whatever of the sea, but was built, as indeed her Uncle Philip had told her most country houses in the island were, without any attempt to take advantage of the natural beauties abounding around them. But, though shut out from all prospect of the lovely scenery in its immediate vicinity, the house interested Mary greatly: partly from its evident antiquity, partly from its picturesque appearance, and partly, no doubt, from the way in which her uncle had spoken of it. Seating herself on the low wall that surrounded the garden—if such a name might be applied to the unkept piece of ground around the house, in which, however, all sorts of shrubs and flowers, roses, sunflowers, laurel, myrtle and stocks, were growing in the wildest luxuriance—Mary fixed her eyes on the object that had first especially attracted her attention—the doorway, with its semi-circular granite arch, which the captain had told her had probably stood there for several centuries.

She was wondering into what sort of a place this doorway led, and what style of inmates she would find within, if only she could gratify her curiosity by entering, when an old woman came out, and took her way slowly along a narrow path leading through the garden to a field behind. Mary had already observed a cow tethered there—as the captain had told her all cows in this strange island were. To prevent any waste of grass, they were only allowed a range of a few feet, and were moved three or four times a day. No doubt the old woman was going to move her cow now, and Mary perceived, with satisfaction, that though she passed pretty close to her, she did not observe her, which enabled her to watch her more attentively; and a most wonderful old woman she looked to Mary's eye, altogether worthy of the careful consideration which Mary bestowed upon her as she hobbled along.

She was dressed in a black stuff petticoat, evidently her best Sunday petticoat once, for it was thickly and beautifully quilted; but now that the black, carefully preserved as it had been, had turned to brown, taken into daily wear. Over this was a short gown, of a print material, of a chintz pattern, the bodice of which, open in front to the waist, exhibited the red handkerchief worn instead of a habit-shirt. The stockings, like her aunt's, were of coarse worsted, only these were blue instead of black; and, instead of shoes, she wore wooden sabots, pointed at the top. Mary's interest, however, centred in the bonnet, or hat—she did not know which it was to be considered—which, like the petticoat, looked as though it had seen better days, and had been originally intended to be worn on high days and holidays, rather than for such purposes as moving cows in a lonely field. It was a most complicated piece of mechanism. The crown, which was shaped like an ancient helmet, was made of silk—very rusty now—gathered into three oval-shaped rows of plaits from the front to the back, ornamented between the folds with lace, real, but rusty also; one very large rosette, of narrow satin ribbon, was placed in front, and a similar one was perched on the very top of the flat crown. Underneath this extraordinary arrangement, the old lady wore a mob-cap, with a very narrow border of white muslin—it was, Mary observed, very white—which was quite plain across the forehead, but quilled from the ears to the chin, and fitted close round a face which Mary thought must have been exceedingly pretty, probably seventy years ago—the features were so regular, and the eyes so dark; perhaps they looked all the darker now, from the snow-white hair which appeared above them, and which was as white as the muslin cap that covered it.