Parsnips

La ponais, Guernsey's favourite crop (you thought it was the tomato, didn't you!) From Bellamy's Guide to Guernsey, 1843, pp. 130 ff.; the woodcuts in this charming volume are by Thomas Bellamy himself; and Duncan's famous The history of Guernsey: with occasional notices of Jersey, Alderney, and Sark, and biographical sketches, 1841. Frank Dally, in 1860, claimed that 'before the potato disease of 1845 the potato [as opposed to the parsnip] was the staple root of tillage, particularly in Guernsey, since which time it has very much declined.'

A p'tit pourche grosse panais (from Guernsey Folk Lore).

The country about the Forest church consists of a stiff but active soil, and in many parts a rich loam. Sylvan beauty ornaments the country occasionally, and furze hedges more or less disappear for those of thorn and other bushes. Parsnip crops in this quarter are about 17,600 lbs. per vergée, provided they are grown in a putrid, dry, sandy soil, of which there is many a field. The Cocquaine1parsnip thrives best in the deep sandy loam of the Valle, where it sometimes attains the extraordinary length of four feet, and in circumference generally from eight to twelve inches. The leaves of this variety grow to a considerable height, and proceed to the whole crown of the root. The Lisbonaise gains in weight and substance what the other does in length, and consequently does not require the depth of soil. The leaves of this species are small and short, and only break from the centre in which there is a hollow cup, and the root tapers away in abrupt ringlets.

As a stranger can scarce fail to be awakened as the bustle attendant on the preparation of the ground for this seed, together with the holiday-like supper at the end, it will not be amiss to take a brief survey of the operations. As the small farms in to which Guernsey is divided will not allow every individual famer to keep sufficient cattle for this work, it is performed by a combination of neighbours, who are repaid by the like joint-stock assistance, in which there is a mutual understanding as to the loan of ploughs and other instruments. Towards the latter end of February the ground is prepared by means of ploughs; a small one precedes, and opens the furrow to the depth of four inches, and a large one follows, with four or six oxen and as many horses, that deepens the furrow to twelve or fourteen inches; this plough is called la grande charrue. As soon as the clods are capable of being broken, the harrowing commences, which is repeated till the soil is pulverised and reduced nearly to a state of garden mould. The seed is than broad-cast over the ground, but on a day when the wind is just sufficient to ensure an even dispersion; after which it is covered with the harrow. The quantity sown to the vergée is half a denerel or two quarts.2

From Duncan's The History of Guernsey, pp. 295 ff.

Field roots for cattle are equally productive. Parsnips are no where grown with more success than in the island, and are probably, on the whole, the best crop that can be cultivated. It is true that mangelwurzel gives heavier crops, and it is almost equally useful for milch cows, but for the fatting of stock of all kinds they are not to be compared to parsnips. The mode of cultivating the parsnip in Guernsey is well described by Dr. John Macculloch, in his communication to the Caledonian Horticultural Society, in September, 1814. He was of opinion that it would form a material and valuable addition to the system of green crops, when it became better known; but it is chiefly on account of the power which it possesses of resisting the injuries of frost, that he points it out as an object of attention to the society. The produce, per acre, is considerably greater than that of the carrot. A good crop in Guernsey is considered about twenty-two tons per English acre. This is a less heavy crop than turnip, but it is much more considerable than that either of the carrot or potatoe; and if we consider that the quantity of saccharine, mucilaginous, and, generally speaking, of nutritious matter in the parsnip, bears a far larger proportion to the water than it does in the turnip, its superiority in point of produce will appear, in this case also, to be greater. The allowance for fatting an ox is one hundred and twenty per day, exclusive of hay; it is found to fatten quicker than when fed with any other root, and the meat turns out more sweet and delicate. Hogs prefer this root to all others, and make excellent pork, but the boiling of the root renders the bacon flabby. The animal can be fattened in six weeks on this food.

Guernsey and Jersey Magazine, Vol. I (1836), p. 243.

Too much can hardly be said in favour of the parsnip, or of the beef and pork fatted with that root. The meat sold in the Guernsey market about Christmas has no superior. The late dean of the island, the Rev. Mr. Durand, who was near ninety when he died, used to relate, that in his younger days he was invited to dine at an agricultural dinner in Hampshire, when some of the party, who had been in Guernsey, extolled the beef of that island: a dinner was betted, Guernsey against Leadenhall, and the dean was requested to send at Christmas a round and a sirloin from Guernsey: the opposite side procured the best that could be had in Leadenhall market. At the trial dinner, the superior excellence of the Guernsey beef was generally, if not unanimously, admitted.

On the 10th January, 1834, there was exhibited in the Guernsey market, a porker of twenty-two months, weighing near seven hundred and thirty-three English pounds, which had never eaten any thing but raw parsnips and sour milk: finer meat was never seen. In the use of parsnips one caution is absolutely necessary. They ought never to be washed, but to be given as they are taken up from the ground; used in that way, they are found not to surfeit the hogs and cattle, and to fatten them better and quicker than they otherwise would; if washed, they are apt to satiate, and will, the farmers say, never thoroughly fatten.

See also Jacob's Annals p. 188, for the cultivation of parsnips and the possibility of manufacturing parsnip wine in Guernsey.

1 Lindley says in his 1831 A guide to the orchard and kitchen garden; or, An account of ... fruit and vegetables:

The following sorts have been cultivated in the Horticultural Garden at Chiswick: —

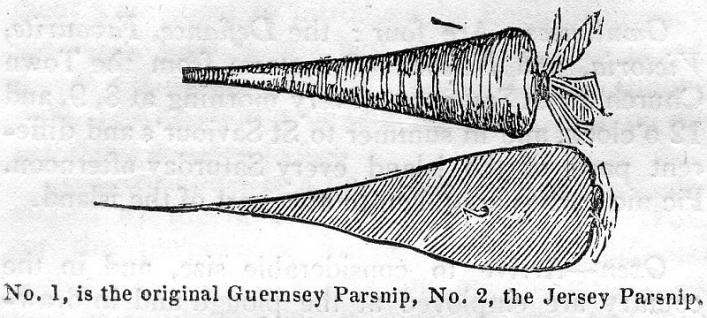

1. Common Parsnip. Swelling Parnsip. Large swelling Parsnip.

2. Guernsey Parsnip. Panais long, of the French. Panais coquin, of Guernsey.

3. Hollow-crowned Parsnip. Hollow-headed. Panais Lisbonais, of Guernsey.

4. Turnip-rooted. Panais rond.

The Guernsey Parsnip, No. 2. appears to be an improved variety of the common sort: it sometimes grows in Guernsey to the length of four feet. The third sort also grows to a large size, and appears to be the most deserving of cultivation, being very hardy, tender in its flesh, and of a most excellent flavour. See also 'Description of the different Varieties of Parsneps, cultivated in the Garden of the Horticultural Society of London.' By Mr. Andrew Mathews, A.L.S. Trans. Horticultural Society of London, VI (1826). Read December 6, 1825.

² This is a précis of Dr. John MacCulloch's long and detailed article of 1814, published in Volume I of the Memoirs of the Caledonian Horticultural Society in 1819, which is referred to above by Duncan. Marie de Garis has interesting comments to make on la pônais and its cultivation in her Dictiounnaire Angllais-Guernesiais, p. 126. See The Guernsey Farmhouse, published by The Guernsey Society in 1963, pp. 115-118.