September 1658: A petition to Richard Cromwell

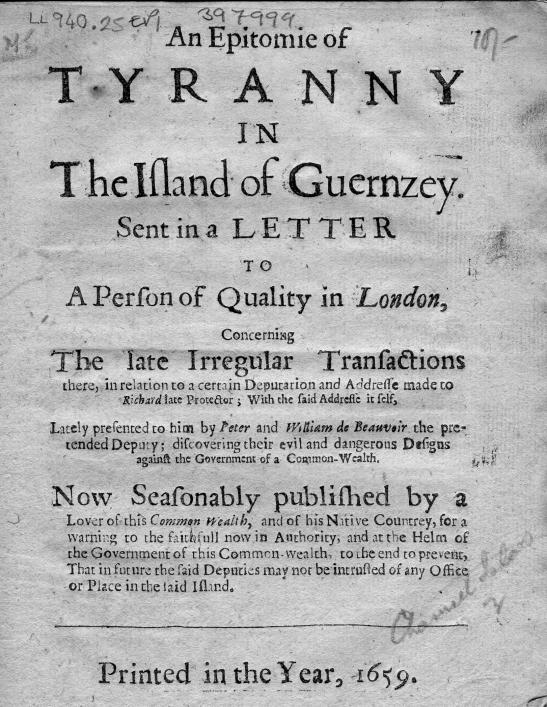

Oliver Cromwell died on September 3, 1658. The States sought to send an address of condolence and loyalty to his son, 'his highness' Richard Cromwell, but were prevented from doing so by the Lieutenant-Governor, Captain Charles Waterhouse, who found their petition 'too submissive.' The leader of the republican party, Pierre De Beauvoir des Granges (1599-1678) and William De Beauvoir du Hoummet, potentially a less committed republican, wrote a defiant letter to Waterhouse, pointing out the Guernsey public's many grievances against him, and proceeded to sneak out of Guernsey and present their petition to Cromwell anyway, taking the opportunity to plead for the unpopular Des Granges to remain as Bailiff. Their actions prompted the publication of a pamphlet, An epitomie of tyranny in the island of Guernsey, which can be found in the Library. It was published anonymously at the beginning of 1659, and accuses the De Beauvoirs of all kinds of misdemeanors.

To his most serene highness, Richard, lord protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland, and of the dominions which belong to it; the humble petition of the bailiff, justices, town council, and others, well affectioned inhabitants of the island of Guernsey.1

In all humility representing that, having deeply shared the general consternation all well-affectioned persons experienced on the death of his late most renowned highness, they have also participated in the great exaltation which possesses the hearts of all those who profess piety, and see your highness act in your government for God and his people. And as your humble petitioners hold nothing more precious than their fidelity to your highness, so they consider nothing so certain as the grace and bounty of your highness, which has emboldened them to prostrate themselves in all humility before your highness, most humbly supplicating that you will be pleased to confirm their privileges, franchises, and immunities which they enjoy by virtue of their ancient charters;2 and, considering that the population of this island has so much increased, that more than six thousand persons earn their living by making worsted stockings and other articles in wool,3 and that one thousand todds of wool are the least quantity to keep them at work, which quantity being equally divided among the number of persons mentioned, only gives four pounds and a half to each individual in a year; we most humbly pray your highness that you may be pleased, out of your favour, to grant to the poor inhabitants of your said isle, the same indulgence and grace already bestowed on the inhabitants of Jersey, by the very noble father of your highness, of happy memory, for the sake of the cordial affection that they bear to your highness. And according to their duty, they will pray God to continue his benediction on the person, posterity, and government of your highness.

Thus read the 'submissive' petition. Three years later opinions were quite different in Guernsey: see May 1661: Cromwell is erased from memory. The rifts in Guernsey society caused by the Civil War are illustrated by E B Moullin in 'Josué Le Roy,' Report & Trans. Société Guern., 1951, p. 120: 'It helps to portray the atmosphere in which Josué [son of the Royalist diarist Pierre Le Roy] spent his boyhood to remember that Charles II decreed in August 1660 that a Mr Peter de Beauvoir should be made Greffier in recognition of the sufferings, in the Royalist cause, of Thomas de Beauvoir, his father. This Royalist Thomas was first cousin of Peter de Beauvoir des Granges, who was virtually the leader of the Parliamentary revolution in Guernsey [and the author of the above letter]: thus do we get a glimpse of the bitter family divisions which must have been common in Josué's boyhood.'

At the accession of Charles II, none other than the two De Beauvoirs, Du Hommet [Hoummet] and Des Granges, were deputed, one to greet and one to petition the new king, along with the Stuart grandee Henry de Vic. Du Hommet was rejected and a replacement had to be found, at the instigation of Charles Waterhouse, who, in a letter to Amias Andros, accuses Du Hommet of insubordination and false representation, probably because he had taken it upon himself to ask that Des Granges remain in post as Bailiff. In fact, in the Library's contemporary pamphlet An epitomie of tyranny in the island of Guernsey, published in 1659, the anonymous author rails at des Granges, as Bailiff, and du Hommet, as a jurat, for taking it upon themselves to deliver the petition in person to Richard Cromwell without having been officially deputised, and for being secret enemies of Parliament. They have no real evidence to indict Pierre de Beauvoir on that last charge, as he was indeed a bullying zealot, 'a man of strange temper and disposition,' who had already at the behest of the States personally petitioned Oliver Cromwell in London on their behalf in 1650; but there is a concrete accusation levelled against the 'debauched' William de Beauvoir du Hommet, that he had left Guernsey and gone to fight in Italy with Lord Downs, a Royalist commander and member of the Stuart family. Serving abroad was often the chosen path of exiled Guernsey Royalists during the war, so this is not completely implausible; his changing sides would go some way towards explaining why he was singled out for the venom of Amias Andros and even Charles II himself. An charge of such an extraordinary volte-face, however, made against a member of possibly the most die-hard Puritan family in Guernsey is hardly credible; William was the grandson of the first prominent Calvinist layman in Guernsey, the bailiff William de Beauvoir, who had been exiled for his beliefs.

George Lee, in his edition of the Notebook of Pierre Le Roy, observed: 'Amias Andros, Seigneur of Saumarez, had always been a supporter of the Stuart cause. Mr Peter de Beauvoir, des Granges, had been a parliamentarian, but was perhaps more opposed to the arbitrary rule of Charles I than to the monarchical government in general. At all events he was no very warm supporter of Cromwell.' Edith Carey added a note to this by George Métivier: 'The family of Monsieur Andros, Seigneur de Saumarez, the jurat Brehaut, of Torteval, and Monsieur Josué Gosselin of St Pierre Port, were pretty much the only people who did not line up behind the banner of the English Republic.' However, Le Roy tells us that a few days after the return of the deputation to the King, the jurats were summoned to Castle Cornet and six were sacked: these were 'Messrs Jean Fautrart, Josué Gosselin, Jean Bonamy, André Monamy, Jean Le Mesurier and Jacques Guille of St George.' They were replaced with Messrs Charles Andros, Seigneur d'Anneville, Elizée de Saumarez, Daniel de Beauvoir, Seigneur du Manoir, Jacques Carey, Jean Blondel of St Savour's, and Mr Jean Brehaut of Torteval, who had been deposed by the Parliamentarians and who now remains senior jurat (le premier Justicier).' Josué Gosselin died in October 1661.

Another indication of division in the Guernsey ranks comes from Sir Peter Osborne, in a letter to Prince Charles in Jersey on 8 September 1648. There were plans for Jersey to attack Guernsey, and Sir Peter, besieged in Castle Cornet, was understandably encouraging them. Bearing in mind that he may have been exaggerating, misinformed, or lying, or any combination of the three, this is Sir Peter's account to the Prince of the state of things in Guernsey:

Suffer not therefore, I beseech your Highness, this coale longer to smoke, but let it be quencht and quickly put out; who are best ruled by being taught to know themselves, which growne proude with forbearance, they do not yet. The towne, as I am informed, are like onely to make opposition. The rest, which are the more considerable number, will doe nothing. And though Russel be returned, he hath no command. They contemne his authority and refuse to obey his orders he hath brought. Sir, you see the ennimy you are to deal with. A people disorderly and divided: hating those that rule them, and yet not knowing what to doe themselves. [Hoskins, Charles II in the Channel Islands, Vol. II, p. 216.]

In February 1644, Peter Carey had been forced to write to Lord Warwick asking for help to quell a mutiny of 'on the part of the common people against your Lieutenant and those well affected towards the Parliament,' which he was worried would have 'serious consequences' if not surpressed. They were lucky that one of Sir Peter Osborne's supporters, Richard Robin, got drunk and revealed the plot; the mutiny came to nothing, but resentment continued to bubble under the surface; the garrison of the island was paid for by the islanders, who were not happy about what they saw as the excessive and unfair cost—such charges did not apply in England.

1 Translation from Duncan's History of Guernsey, pp. 105 f., in the Library. Waterhouse became Lieutenant-Governor in 1654.

2 Richard Cromwell did not, however, get the full treatment: 'In 1625, the year that Charles I came to the throne, Monsieur Jean de la Marche was appointed to the Church of St Peter Port, Monsieur Pierre Painsec having apparently removed to the Castel parish. Immediately on his entering on this charge, Mr de la Marche proceeded to London with Mr Amice de Carteret, Bailiff, as deputies of the States, to solicit a renewal and confirmation of our charters, as was usual at that time, on the accession of a new monarch.' [St Peter Port Parish Magazine, August 1870, in History of the Guernsey Churches, Staff.] See also the accession of Charles II where unsurprisingly even more fuss was made.

3 See Petition of December 20th 1660 to Charles II, from Jersey, Guernsey, Sark and Alderney, in response to the Bill for prohibiting/transporting of wool and wool fells: 'The only livelihood and subsistence of above fifty thousand persons in the islands depend upon the manufacture of woollen stockings. The Kings of England have been pleased time out of mind to grant the inhabitants several competent quantities of wool towards this manufacture, without which the poor people must be reduced to an inevitable starving. His Majesty has lately confirmed by his proclamation two thousand todds of wool for Jersey, one thousand for Guernsey, two hundred for Alderney, and one hundred for Sark, this being the least quantity they have need of. The petitioners pray their Lordships to preserve the inhabitants in the possession of that gracious grant, without which the Islands cannot subsist or avoid utter ruin.' [7th Rep. of Hist. MSS Com.] Act of the Royal Court, June 1616, 500 tods of wool requested from England by Pierre de Beauvoir and Thomas Leach, granted 1622.