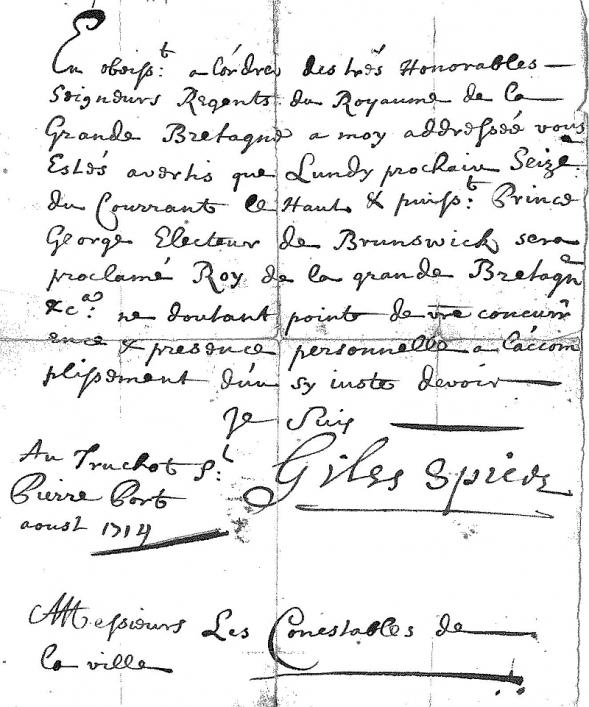

A prince of their own choosing: the proclamation of George I, 16 August 1714

A translation of part of Laurent Carey's manuscript On the Customary Law of Guernsey, from the Guernsey and Jersey Magazine, Vol. V, 1838, edited by F. B. Tupper. Carey's Essai, written around the 1750s, formed the day-to-day reference for the proceedings of the Royal Court, under whose auspices it was eventually published in 1889. Here he was illustrating the fact that the inhabitants of Guernsey can choose to accept the proposed sovereign or not, who, once accepted, becomes 'un prince de leur propre choix'—and display absolute loyalty when they do so. The photograph below shows the proclamation of George V in Guernsey in 1910. The letter above is an invitation from the Governor to the constables to attend the proclamation of 1714. Library collection.

Although this island has followed the fortunes of England in all the revolutions which have there occurred, and although all the kings who have reigned there since the Norman conquest, have also been our sovereigns, that is not a sufficient reason why we should form a part and parcel of that kingdom; for the kings of England, to whom Normandy was subject, have not transmitted to their successors a title to the crown of England, more legitimate than to the ducal crown of Normandy; their right to both were the same, both being hereditary, and both having descended from the same prince, who was their common sovereign. [...] this island always remained tranquil, nor did any prince ever establish himself here by force; but we have involuntarily obeyed the sovereigns of England, with whom we have been so intimately allied, without, however, being their dependents, for, in gratitude, we could not be otherwise than attached to a state by whom we have been protected and in whose commerce we have participated.

We have pursued the same system in reference to those princes whom the English people have called to the throne, who, though not the nearest heirs to the crown, have been chosen by the English for political reasons. The inhabitants here have not only voluntarily recognized them as their sovereigns, but have accepted them with every demonstration of joy and affection. The marked manner in which they displayed their zeal on the accession of George the First, when he was proclaimed in the island, after intelligence had been received of the demise of Queen Anne, has been recorded in The Annals of George the First, vol. 1, p. 61, in the following terms:

There is one circumstance,' says the annalist, 'so remarkable in the manner in which his majesty was proclaimed at Guernsey, that it merits particular notice, more especially as this little island forms part of the small fragment which remains to England of the Ancient duchy of Normandy, and also because the conduct of the inhabitants, on this memorable occasion, shows not only the great difference of feeling displayed by a people who live under a free government contrasted with that of their brother Normans, who live under a despotism, but it likewise shows the difference among those of our own subjects, who are actuated by loyalty, and those who are not.

"Guernsey, August 4th, 1714. We have heard by a vessel belonging to this island, which arrived on Sunday evening last from St Malo, that, on the preceding day, several merchants of that town had received letters from Paris, announcing the death of her Majesty Queen Anne. [...] On the following morning an English vessel from Salcombe, and another from Topsham, confirmed the news, which threw the whole island into the greatest consternation. The lieutenant-governor, and the royal court immediately assembled,1 and having summoned before them one Pope, master of the above-named vessels, they examined him on oath. He declared that the queen was dead; that he had heard king George proclaimed at Dartmouth, as he had been at London, and that the same ceremony had taken place in different parts of England. Whereupon the lieutenant-governor and the royal court (not wishing to allow any delay in expressing their zeal and loyalty towards his majesty) after the example of their predecessors, resolved to proclaim his majesty king George with all the customary solemnities. The regiment of the Town militia, being assembled under arms, lined the streets to the door of the court house: the lieutenant-governor, the judge delegate, with all the jurats who were in the island, the clergy, the officers of the court, and all the principal inhabitants, proceeded from the residence of the judge delegate to the court house, being preceded by the colours and band of the said regiment, and when each had taken his seat, Peter Martin,2 Esq., judge delegate, or president of the court, delivered the following speech:

Gentlemen,—You all know that we have assembled this day in consequence of the sad and afflicting news received of the death of our august princess, queen Anne, of glorious and triumphant memory, - news which, without doubt, would have plunged you all in the deepest affliction, had it not pleased divine Providence to have interposed in our favour. In fact, had we known, a month since, that the queen would have been this day in her tomb, with what doubts and fears would our hearts have been filled? The future was dark and louring, and the malicious pride, and insolence of the enemies of the state and of the protestant religion had risen to such a pitch, that their machinations seemed certain of success, and that it only depended on themselves, that they should be carried into execution. But, gentlemen, these black and sombre clouds are happily dispersed. God himself has dispersed them, nor do we hear the faintest thunder peal above our heads. He has permitted, in his infinite bounty, that the most high, most puissant, and most excellent Prince George, elector of Brunswick Lunebourg, the legitimate heir of her majesty, be peacably declared king of these realms in his principal city of London, with acclamations of extraordinary joy, and in all the other towns and cities, in which the details of her late majesty have been known. [...] It therefore only remains for us to perform our duty, as good and faithful subjects of his majesty King George, by immediately proclaiming him king in this place and in all other places in which it has been customary to proclaim our princes on similar occasions.

The annalist then makes the following remarks:

His majesty king George was then proclaimed by universal consent, amidst the acclamations of an extraordinary concourse of people, whom the solemnity of the day had drawn together, the roar of cannon from the castle, and discharge of musketry from the troops in garrison, which were answered by the regiment of militia and town artillery. The ceremony being finished, the lieutenant-governor, the royal court, the clergy, etc., partook of a splendid repast, prepared by the order of the royal court, where they drank the healths of his majesty, of his royal highness the prince, and of the other princes and princesses of the blood royal, with several other toasts, expressive of their loyalty to their new sovereign. The bells of the churches rang a merry peal during the day, which terminated by fireworks and illuminations.

The main illustration at the top of this article is an invitation (in the Library's collection) from the Lieutenant-Governor Giles Spicer to the Town Constables to this proclamation and celebration, which took place on August 16th, although the proclamation by the Privy Council in London immediately followed Anne's death on 1st August; the complete letter was written from the Governor's residence in the Truchot.

1 The Fashion Notebook reads: 'Friday 8th April 1625 Charles was solemnly proclaimed our king in this island, the king his father having died on the 27th March preceding.' [From the French, noted Edith Carey in Notebook of Pierre Le Roy, re same year.] From the Actes de Etats, Vol I, we find that the States had sent a letter of condolence to Queen Anne dated April 1 1702, on the death of William III, from 'vôtre isle de Guernesey, partie de vôtre antien Duché de Normandie;' 'comme de bons et fidelles sujets' they assure her that 'nous exposerons en toutes occasions nos biens et nos vies pour soutenir le juste droit de votre Majesté contre tout ses ennemis quy voudront attenter à votre personne sacrée, Etat ou Gouvernement,' recalling the only condition in the Royal Charters incumbent upon Guernseymen, that they should ride to the aid of the monarch should any attempt be made to kidnap him or her.

They do not appear to have sent a letter to George I in 1714, but did send one on 27 June 1726, commiserating with George II on the death of his father, and congratulating him on his ascension to the throne, composed in very flowery English. John Graham, Commander-in-Chief (later Lieutenant-Governor), was present at the States meeting of the 23rd at which 'Mr. Daniel de Beauvoir, Mr. Jean Le Mesurier, and Mr. Thomas Fiot, Jnr.,' were authorised by the States to compose the letter of condolence and congratulation. The States' own report of this meeting is unusually also in English. Three months earlier, with Helier Bonamy presiding, they had addressed a letter in French to George I expressing their horror at Spanish attempts to invade Gibraltar.

2 Pierre Martin, a Jurat, was standing in for the Lieutenant-Bailiff, Eléazar Le Marchant, who never seems to have returned to preside over the court before his death in 1716. Since 1717 John Graham had been Captain of an Independent Corps of Invalids stationed at Guernsey, having entered the service as ensign in 1703/4. He became Lieutenant-Governor in 1735 and held office under the Governor Francis de la Rochefoucauld, Marquis de Montendre, a Huguenot nobleman in the service of England, who, having attained the highest rank possible for a foreigner (that of Marshal) died in 1739, and Lord Percy, who became Governor in 1742; Graham was replaced in 1745 by another Captain of Invalids who had entered the service at the same time, Charles Strahan. 'Died December 14th 1757, Cha. Strahan Esq., Lieutenant-Governor of Guernsey, and Captain of an Independent Company, who has served no less than 53 years with an unblemished reputation.' See Owen, W, Miscellaneous Correspondence, II, 1759, p. 697.