Nicolas De Garis, conscientious objector, 1805

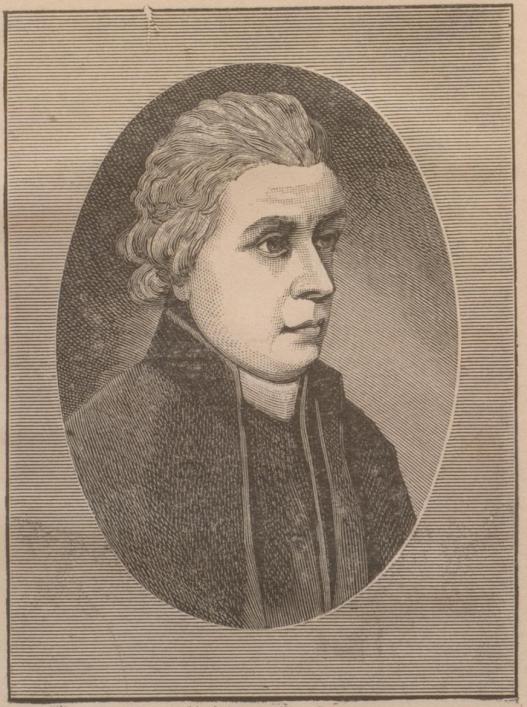

By H D Olivier, from The Guernsey Free Churchman, March 1932, p. 23. 'Not honesty in the abstract but Honest is my name. And I want the kind of person I am to match what I am called.' The portrait is of a sympathizer, Etienne Gibert, Rector of St Andrew, the frontispiece of his biography, published in Toulouse in 1889, by Daniel Benoît, Les Frères Gibert, du désert et du refuge. This book includes the life of his brother Louis, also a Protestant minister, who emigrated to South Carolina.

Obituaries are uninteresting to many people, who thereby lose much, for often even in the dullest and most prosaic records there comes to light some point of real interest, which has been long overlooked or forgotten.

In the obituary notice of a Methodist Local Preacher of the Guernsey and Sark (French) Circuit, written sixty years ago in a book kept for the specific purpose of recording such notices, the following words occur: ‘Notre ami défunt fut appellé à porter dans son corps les marques du Seigneur Jésus,’ which can best be translated thus: ‘Our deceased friend was called upon to bear on his body the marks of the Lord Jesus.’

Why were these words written, and what is the story behind them?

In the mighty revival of the work of God throughout England in the 18th century under the leadership of the Wesleys, with Whitefield, Fletcher, and their many other co-adjutors, the Channel Islands played their part. John Wesley himself, though well advanced in years, visited the three islands of our little archipelago.

One of the effects of the revival was to lead those whose hearts had been greatly stirred by the Spirit to have a much greater reverence for Sunday as a day of rest and worship than was usual among other people. They could not reconcile the call to military training and service on Sunday with the dictates of their conscience as to the sacredness of the day, especially as weekdays were available for that purpose.

Methodists in Jersey, Guernsey and Alderney suffered imprisonment rather than go against their conscience. The resultant difficulties lasted some years, but eventually the spirit of tolerance prevailed and by the end of the 18th century it was generally accepted that these men should be allowed to drill on weekdays instead of Sundays.

Complete victory over intolerance had not yet been secured, however, for we find that as late as 1805 the excellent Rector of St Andrews, Etienne Gibert,¹ interceded, unsuccessfully at first, with the ruling powers to permit some of his own flock to be exempt from military service on Sundays.

Nicolas De Garis, the local preacher from whose obituary notice we have already quoted, was born on 10 January 1789, at Les Raies, in St Saviour’s parish. He was led to see his need of a saviour through the ministrations of the Rector of his parish, the Rev. Thomas Carey. Eventually, however, he joined the Methodist Society when he was about 21 years of age. A local Methodist preacher, Mr Ozanne, under the spirit of God, led him into light and liberty.

When in 1805 the Reverend Etienne Gibert took action, as mentioned above, Nicolas De Garis could scarcely have been of military age, although he must have been enrolled and called up for duty not many years after. He refused to bear arms on Sundays and as a result he was imprisoned with two of his friends in Castle Cornet. They were not detained many days: their scruples were respected and, being liberated, they were allowed to drill on weekdays.

Our hero’s name may not be enshrined in the annals of his country as that of some great warrior, philanthropist, statesman, or other notable. He may have been but a simple unlettered farmer; he may have worn corduroy trousers; he may have gone au vraic auve sa k’Maiseole de bien Molton (a long smock made of blue Molton often worn in those days when gathering seaweed); his sermons may have been very homely talks, but when he died on 29 December, 1871, it could not be said that he had lived in vain, for he belonged to that class of men to whom we are indebted for much of that measure of religious liberty which we enjoy today.

It is not within the purpose of this article to discuss the present aspect of Sunday observance, and it is doubtful whether any good purpose would be served thereby. We may not altogether agree with the viewpoint of our forefathers, and may look at these matters from a different angle from theirs, yet we cannot but greatly admire their fidelity to conscience. These were men of great depth.

As we read the stories of their lives, does it not strike us that we might do well to ask ourselves whether we possess their spirit of determined opposition to anything that contradicts eternal spiritual values and principles. These days, too, circumstances may occur in which we are called on to demonstrate such spirit.

¹

It is natural for a Minister of the Gospel as humble and devoted as Gibert to maintain friendly relations with others who fight in the Lord's army, no matter under what banner it may be. Just as he had linked himself closely with the Moravians in Bordeaux, so would he therefore show the same sympathy towards the Guernsey Methodists, whose earliest works in Guernsey virtually coincided with his arrival in the island. Jean De Queteville first landed in St Peter Port on 18 February 1786, when he began those evangelical tours which were to have so blessed an outcome. Gibert became friends with this man of God, and De Queteville seems to have been the author of the short notice about the refugee pastor, published in the Magasin Wesleyen. Gibert did not emulate the behaviour of so many other Anglican priests, who not only refused to have anything to do with the Methodists, but did everything possible to frustrate their work. 'Far from pushing them away, and treating them with the cold disdain they generally met with from ministers,' writes Mr Matthieu LeLièvre, 'he welcomed them as fellow fighters against sin and unbelief.' [Benoît, op. cit., pp. 349-350.]