Devotedly loyal islands in collision with the Government, 1845

10th May 2017

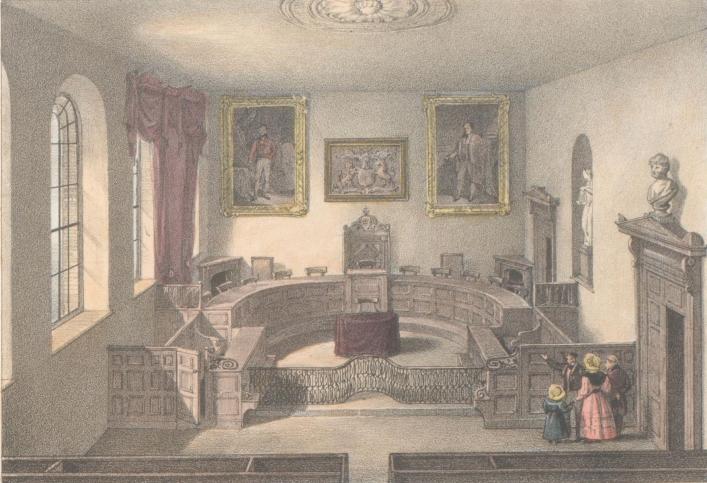

The Eclectic Review, Vol 17 (1), 1845, pp. 540-555. 1848 is the year of revolution in Europe; in Guernsey the stirrings of the people, such as they were, occurred just a few years earlier. (The headings have been added for ease of reading.) The illustration is a print from the Library Collection dated c 1835, published by M Moss, and showing the interior of the Royal Court in St Peter Port. 'May this people ever beware of apeing the follies of their neighbours, and retain their own dignified simplicity! For it they are pre-eminent. Should they ever stoop to become imitators, they can never get beyond an humble mimicry of that which is useless and effeminate in the customs of England.'

Art. II. The History of Guernsey; with occasional Notices of Jersey, Alderney, and Sark. By Jonathan Duncan, Esq., B.A. London: Longman and Co. 8vo. pp. 654.

2. A Letter addressed to Mr. Advocate Tupper, in Vindication of the Conduct of Major-General Napier, Lieutenant-Governor of Guernsey. By J. Bowditch. Jefferys and Co., 123, Chancery Lane.

3. Observations of Advocate Tupper, of Guernsey, in Answer to Mr. Bowditch. Guernsey. Brouard.

4. Authentic Report of the Evidence taken before the Royal Court of the Island of Guernsey, relative to certain Charges of Conspiracy and Sedition. Also of the Trials instituted thereon; and of the Correspondence between the Royal Court and Her Majesty's Government, from the 4th day of June to the 10th day of August, 1844; taken chiefly from the Records of the Royal Court. Guernsey: Brouard.

Mr. Duncan's volume, named above, was published in the year 1841. The principal materials for it were derived from orders in council, acts of parliament, and ordinances of the Royal Court of Guernsey. The work is highly creditable to the research and ability of the author; and is, we think, quite a model of the most useful kind of historical composition. The writer's aim evidently was to state facts, rather than to give opinions. He has often been referred to as an authority, in the recent pleadings before the Privy Council. It may be right to add, that the book is neither a cheap, nor a popular one. Its very excellence renders it a book for the few. [There are copies in the Library.]

Most of the readers of this journal were taught at school to name, as among the British possessions, Jersey, Guernsey, Alderney, and Sark: yet till recently little more was known of these places, than of the Falkland Islands, or the Azores. Mr. Inglis's work on the Channel Islands excited much attention, and considerably increased the number of visitors to the scenes he described: but the great majority of even intelligent people in this country are still ignorant of the history, character, and customs, of the islanders, who, dwelling within the arms of a French bay, are among the most devotedly loyal of all the subjects of Britain: and who, living under the same sceptre as ourselves, and near to our own shores, are free from the burden of debt, of heavy taxes, of a landed aristocracy, of a standing army, of an expensive administration. The simple institutions of these people well deserve the study of statesmen.

The happiest community, which it has ever been my lot to fall in with, is to be found in the little island of Guernsey . . . . . . How is it that Guernsey should be so much ahead in the career of happiness? Guernsey has superior laws — superior institutions

So wrote, in 1832, Frederic Hill, Esqr., the government inspector of prisons, who had twice visited the island under circumstances favourable for becoming acquainted with its condition. Nothing has since occurred to render inapplicable his glowing eulogium.

During the past year, the island authorities have been brought, several times, into collision with the imperial government; and public attention has thus been directed to them. Some account of the islands, and the recent disputes connected with them, will not therefore be deemed unseasonable, or uninteresting.

Nearly 100 miles to the south west of Southampton is Alderney, an island about eight miles in circuit. Twenty miles further in the same direction is Guernsey, which is nine and a half miles long, and five and a half in extreme breadth; and no spot in which is more than two miles from the sea. Still twenty miles onward—or reckoning from port to port thirty—and bearing to the south-east, is Jersey, twelve miles in length, and seven in extreme breadth. Between the two last-mentioned places, is the remarkable little island of Sark; and between Sark and Guernsey are Herm and Jethou, mere rocks covered with scanty herbage, and having, the former, but a few houses upon it, the latter three only. As seen from Guernsey, the appearance of these various islands, studding the sea, and becoming more or less distinct with every change of the atmosphere, and every alternation of light and shade, is exceedingly picturesque.

By every one, who has admired the 'tall ancestral trees' of England, the want of timber is at once felt as a great deficiency in the Channel Islands. Whether it be owing to the absence of all shelter from the winds, or to other causes, we are unable to say; but not one fine tree, like the forest trees of our own country, is any where to be seen. With this exception, however, the traveller will find little to check his admiration, and very much to awaken it. To those who wish for the mild but bracing air of the sea, it were difficult to select more agreeable places of resort. All the islands excepting Alderney—with which there is no regular steam communication—are easily accessible: and if our readers purpose to repair, for a month or so, to the vicinity of the sea, we can assure them that they will be highly gratified by a trip to the Channel Islands. At an expense, scarcely greater, perhaps less, than that incurred by a sojourn at Ramsgate or Brighton, they may combine, with saline breezes in perfection, scenery beautiful and varied, and a state of society which, to an Englishman, is novel and instructive.

The largest of these islands, Jersey, is the most populous and lively. In the interior it is well wooded, though the trees are not large; well cultivated; and pleasantly diversified. Some of its views are surpassingly beautiful. From Prince's Tower, for example, where the eye commands a considerable part of the island, and, looking across the sea, discerns a long range of the French coast, and on a clear day may distinguish the cathedral of Coutances, the stranger tears himself away with great reluctance.

Sark is a mountain three miles long and one broad, rising around its whole circumference, precipitously from the sea; and is accessible on the one side, only by the aid of a rope; on the other, by landing in a small nook, where a tunnel bored under the beetling rock, leads to the upper part of the island.

As the voyager approaches Guernsey, he sees St. Peter's Port, its only town, nestling in the bosom of a small bay. The houses come down to the beach, and cover the side and crown the summit of the rather high and steep ascent; being, on the rising ground, very generally interspersed with gardens and greenhouses. The suburbs of the town surprise the visitor, by the number of genteel residences they contain, each one adorned with luxuriant evergreens and flowers. In the interior of the island are several villages; and though the population is four times as dense as in Ireland, there is no crowding. Every cottage has its garden, which is well stored with shrubs and flowers, and very rarely neglected. Indeed, the passion for gardening, ornamental as well as useful, is among the most striking characteristics of the natives of this charming island. They are distinguished also by simplicity, honesty, enterprise, and independence. Existence among them is enjoyed, not endured; and certainly, as compared with the people of our own beloved but misgoverned country, they are a thriving, contented, and happy race.* [*Barbet's Guide to Guernsey will be found a very useful handbook. Unlike the generality of books of its class, it is filled with really useful information, and without the ordinary intermixture of garish description and bad poetry. We may mention also a very usefully constructed, and cheap pocket map, published by Moss.]

The coast scenery of all these islands is captivating. Here, the traveller pursues his way through a deep and winding valley, to the quiet and sandy beach. There, he climbs to the edge of the abyss, and seating himself on a huge crag, looks far down on the rock-bound coast, and finds a strange delight in the sweep and shriek of the sea-gull, and the cauldron overflowing with the foam of the wildest surges. Or yonder, with careful footsteps, he picks his way along the steep and rugged descent, till he finds himself by the water's edge, with stupendous precipices of solid rock towering behind him, a wild cavern yawning at his right hand, the beach strewed with rocky fragments of every size and form, while here and there a vast pile of rock stands bare and erect amidst the spray.

At the time of the Conquest, the Channel Islands were a part of the duchy of Normandy; and they remained so, as long as the English kings held possession of that province. When John lost his continental territory, the islanders remained faithful to him. Being thus completely severed from the seat of government at Rouen, it became necessary to give them new laws. These were framed according to Norman customs, and are to this day styled the constitutions of King John. If a Guernseyman be asked when his country became subject to England, his quick reply is, that England is the subjected country, and that the Normans were the conquerors. Many of the ancient customs and privileges still exist; and the ancient language, Norman French, still struggles, though in vain, for the precedency.

Local government

The institutions of the several islands are substantially the same. It will suffice, therefore, to explain those of Guernsey, which have recently undergone a slight reform by a bill, passed in the island legislature on the 9th of June, 1843, and the royal assent to which was communicated on the 26th of December last.

To render the explanation as clear as possible, we will first exhibit the judicial and legislative authorities assembled; and afterwards explain the mode of their appointment.

Will the reader imagine himself crossing the hall of a substantial building, and entering, not at either end but by the side, a moderate sized room? Fine portraits of Sir John Doyle and Lord Seaton, and full length portraits of Lord de Saumarez, and the late eminent bailiff, Daniel De Lisle Brock, Esq., adorn the walls. The room itself is plain, and yet wears an air of thorough respectability. To the left of the visitor, as he enters, there rise from the floor, seats for perhaps two hundred people. At his right there are also seats arranged for official persons. This is the court-house, where justice is administered. It is also the parliament house.

Suppose the proceedings to be judicial. At his right, the visitor observes on a raised and distinguished seat the bailiff, who is the highest civil functionary on the island, and has a salary of £300 a year. On the right and left of the bailiff are other gentlemen, not less than seven; if all are present, twelve. These are called jurats. Together with the bailiff, they act in all important civil and criminal causes, as both judge and jury: and from their decision there is no appeal excepting to the queen in council. Below the bailiff and jurats, and at their right hand, is the attorney-general, who has a salary of £200 yearly: at their left and before them, are seats for the advocates and others connected with the causes tried. Such is the court of justice. The proceedings are carried on in the French language, but witnesses are examined in English, if they speak it. The jurats listen to the pleadings and the evidence; question the witnesses if they think it necessary; and when the trial is completed, give their verdict aloud, one by one, generally assigning the reasons for it. The bailiff commonly gives a summary of the cause; and then pronounces the opinion of the majority of the jurats, which is the sentence of the court. If there be an equality of votes, the bailiff has a casting vote. There is no display in the court house. Neither counsel nor judges wear any official dress. The proceedings are marked by much less technicality, and much more common sense, than our own courts of justice. May this people ever beware of apeing the follies of their neighbours, and retain their own dignified simplicity! For it they are pre-eminent. Should they ever stoop to become imitators, they can never get beyond an humble mimicry of that which is useless and effeminate in the customs of England.

Enter the same place when the legislature, or 'States of Deliberation,' are assembled: and, if all the members be present, there are the bailiff, the twelve jurats, eight rectors of parishes, the attorney-general, six deputies of St. Peter's Port, and nine deputies from the other parishes: in all thirty-seven. That is the parliament. In cases where a question is not decided by two-thirds of the members present, the president (the bailiff) may, if he think fit, submit it a second time, within one month, when it is decided by a majority of votes. By this body the general affairs of the island, including its taxation, are managed. Its proceedings are public by sufferance. The military governor—of whom more will be said hereafter—has a right to be present and speak, but not to vote. The relation of this local legislature to the British parliament, has given rise to some serious difficulties; and would, but for the spirit of the inhabitants, and their ancient and cherished charters, have sunk the people into thorough dependence and beggary.

It will be observed that the bailiff, jurats, and attorney general, are functionaries both in the judicial court and in the legislature. When they sit as legislators, they are joined by eight clergymen and fifteen deputies. The bailiff and attorney general are appointed by the crown; which appointment, however, is commonly a formal way of executing the wish of the Guernsey authorities. The clergymen sit in the parliament ex officio. The other members are appointed by the people as follows. The rate-payers in the parish choose persons to manage their parochial affairs. These persons elect the deputies in the several parishes. When a jurat dies, the bailiff, the surviving jurats, the attorney-general, the eight clergymen, and all the parochial authorities, form one elective body, for appointing his successor. The appointment is for life, the yearly fees are not more than £15, and the person elected must serve, under pain of imprisonment or expatriation. Every man in Guernsey is bound to serve his country when called upon to do so by the public voice. The same elective body appoints the sheriff, to whose office there is annexed a salary of uncertain amount. The entire number of electors is 222; but it will be borne in mind that they never act as a body, excepting in the choice of a jurat or sheriff.

The mode of electing the deputies requires and deserves a little further explanation. In each of the country parishes, the rate-payers choose yearly two constables. The same parties choose also other officers called douzeniers, the number of the latter being generally twelve. They are chosen for life: their service is compulsory and without pay. No one is qualified for the office who has not been constable. These constables and douzeniers regulate the parochial assessments. In the collection of such taxes as are levied on property, they occupy the place of the income-tax commissioners in England, and their task is usually an easy one. They also attend to the streets, roads, boundaries, drainage, &c. In short, they are a sort of corporation in each parish; the senior constable being the chairman of their meetings. By the recent Reform Bill, the populous and wealthy parish of St. Peter's Port is to have five such corporate bodies; but the parochial authority is to remain almost exclusively with one of the five.

The number, then, of these corporations—so we may call them—is fourteen; namely, one for each of the country parishes, and five for the town. Of these, one sends two deputies to the legislature; the remaining thirteen return one deputy each. The election is for one session only, there being several sessions during the year.

Militia

Every man in Guernsey, unless in very special cases of exemption, is trained to arms; and is thus prepared in case of invasion, to defend his rock-bound home. The island is also protected by the dangerous navigation of the surrounding seas —the danger arising both from the rocks and the currents. None but practised and skilful seamen can venture there. If the reader should ever pass from Guernsey to Sark in the neat little cutter which runs between those places daily, he may have an opportunity of admiring the style in which she is made to thread a triangle of rocks, where but for the turn of the helm at the right instant, the vessel must inevitably strike. The English government, however, deeming the island both important and insecure from its proximity to France, has planted cannon all round it, but from their small calibre and short range they would at present prove totally inefficient. On the heights above the town there is an extensive and strong fortification, which cost, certainly more than £200,000, and, we have been told, more than half a million sterling. A military governor—now General W. F. Napier—resides on the island, and the garrison is entirely under his control. He has also the regulation of the island militia, which, during the last war, was very effective. Sir John Doyle said, that with it alone, he would undertake to defend the island against any attack of the French. The garrison expenses, including the erection of the works, are borne by that pay-master general, John Bull. The military governor is the patron of all the church livings.

Legal structures

The mischievous custom of primogeniture and entail, as existing in England, is, in Guernsey, unknown; and the law verges, to say the least, towards a contrary extreme. The owner of landed property may sell it at any time; but, if he have children, he cannot bequeath it. The law divides it among all his children, giving however some advantage to the eldes -son. In consequence of this arrangement, there are no large landed estates, and scarcely any tenants, but a great number of small and independent proprietors. It is delightful to witness the sturdy and dignified manhood of the little cultivators of Guernsey, as contrasted with the servility of too many of the yeomanry of England. The late bailiff, Mr. Brock—one of the most enlightened politicians of modern times—strongly recommended a similar plan of partition, as a panacea for the evils of Ireland. The testimony of such a man, whose views were founded on the experience of three quarters of a century, is weighty. His arguments are clear and conclusive; and may be seen in Mr. Duncan's volume, page 307.

Taxation

The taxation of Guernsey is very light. It may be quickly explained under two heads:—first, the parochial taxation; and secondly, the taxation for the general purposes of government.

The parochial taxation is raised in each parish by the corporation already described, having been previously voted by a general meeting of the rate-payers. It is a property tax. In the country parishes no one is charged with this tax, who has not possessions worth £100. In the town, taxation commences with those who are worth £200. All kinds of property are included in the calculation, even household furniture. This tax amounts to about 3*. 4d. per cent, per annum; and by it provision is made for the poor, and for all other parochial expenses, such as lighting, public pumps, &c. It is humiliating to be compelled to add, that no inconsiderable part of this burden is imposed on the people of Guernsey by the United Kingdom. Mr. Brock, writing in 1840 to Lord Normanby, said:—

Out of 261 inmates (in the town workhouse) 109 are strangers, or born of strangers, almost all of whom are English, Scotch, or Irish, whereas in all England, it would be difficult to find a single Guernsey pauper.

The expenses of the general government are defrayed by publicans' licences, a duty of 1s. a gallon on spirits, and the harbour dues; which together suffice for the payment of salaries, for keeping in repair the excellent roads of the island without any turnpike gates, for coast defences against the inroads of the sea, for public buildings, harbours, &c. The revenue amounts to about £7,500. Should it at any time prove insufficient, the States have the power, by a vote of two-thirds of their number, of levying a small property tax, which would be collected in the same way as the parochial property tax.

The Channel Islands, it will be seen, are free from the intolerable burdens and annoyances of English taxation. There are no custom-house officers to vex the traveller, no excisemen to intrude upon the tradesman: there is no long array of tax gatherers, no host of well paid commissioners. There are no indirect taxes stealthily filching from the purchaser a large part of every shilling he expends. Tenpence is the regular price for three pounds of good moist sugar, excellent coffee is sold for 10d. or 1s. the pound, and good tea at 2s. 5d. And even from these prices a considerable reduction is to be made. The pound weight is more than 17 oz. of our standard, making a difference of 8 per cent.; and English money is always at a considerable premium. These two causes reduce the tea quoted at 2s. 5d. to 2s. English, and other articles in proportion.

Relations with the UK

The islands have repeatedly been troubled by the intermeddling of the British Parliament or Ministry: and well do these parts of their history exemplify the words of Solomon : 'wisdom is a defence.' When England was attempting by the legerdemain of an act of parliament to make a pound note and a shilling worth a guinea, though, de facto, a guinea would buy a pound note and six shillings, the Guernseymen saw no mystery in the currency question, but very wisely determined to say their money was worth, what every body knew it was really worth. Accordingly, in 1811, and again in 1812, the merchants under the presidency of Mr. Brock, unanimously resolved to raise the denominative value of the coin then current among them; and by this natural expedient, they prevented what would otherwise have inevitably followed, the disappearance of a metallic currency from the island. In 1836 Sir R Peel intimated an intention of introducing the British currency into the Channel Islands. Mr Brock, in a letter relating to this proposal, touched the general question of the currency with the hand of a master, shewed the ruinous consequences of Sir R Peel's measure in England, and assigned various special reasons why the contemplated change could not be made in Guernsey: and the affair dropped. In 1821 an act, of which the islanders had no notice, received the royal assent, closing the ports of the Channel Islands against wheat, when it was under 80s in England. This was quite a new thing to people accustomed to have their ports open to the productions of all the world, duty free: and the effect of the measure would have been to raise the price of wheat (as often as the price in England was under 80s) to more than double the price for which, after a good harvest, it sells in the islands: and this too among a people dependent, to a great extent, on foreign growth for their very existence. 'Is it possible,' asked Mr. Brock, 'that any intention should exist to take away the very means of our subsistence?' He came over to England together with one of the jurats, to remonstrate, and the obnoxious clause was repealed the next session. In 1834 the agriculturalists of the West of England complained that foreign corn was smuggled into this country as the produce of the Channel Islands. A blundering report was obtained on the subject, and the President of the Board of Trade, Mr Baring, introduced a bill to deprive the islanders of their ancient right of sending their home grown corn, free of duty, into the English market. Mr Brock again took the field, accompanied by two deputies from Jersey. They obtained a committee of the House of Commons, triumphantly disproved the allegations of the report on which the pending measure was founded, which was in consequence withdrawn. We cannot forbear extracting the conclusion of a long letter, addressed by Mr. Brock to the Right Honourable Henry Goulburn, and bearing date April 9th, 1835, as a specimen of the manly bearing of this enlightened patriot, when approaching the imperial government.

It is unfortunately true, that the agricultural interest is depressed. It is wrong, it is ridiculous, to ascribe any part of that depression to the Channel Islands. The four islands do not contain 25,000 acres fit for cultivation—meadows, orchards, and gardens included. How can this, with any man of reflexion, be held up as an object of jealousy to the landholders, many of whom are owners of estates to a larger extent? Our connexion with England can indeed in no way be injurious to her; her commodities, produce, and manufactures, are freely admitted, to an amount exceeding ten-fold the value of our produce which she so reluctantly takes in return. The trifling quantity of corn exported from the islands, and which the commissioners of customs cannot make to be more than 2,151 quarters of wheat, and 860 quarters of barley, annually from all the islands on the average of five years, is not sufficient to feed one-balf, or anything like one-half, ofthe persons employed in England for the supply of the islands. England trades with no part of the world so advantageously as with the islands, in proportion to their extent. The goods exported by her to the islands amount to at least £500,000, while the produce she takes back does not amount to £120,000;—must we receive all, and send nothing back? Such a system is too barbarous for the 19th century, and how it could enter into the thoughts of those specially appointed for the encouragement of trade is inconceivable. Some persons are disposed to account for it by reasons unconnected with trade, and dependant only on local and agricultural prejudices; if so, it is in vain to argue; and all I must say is, that I cannot think it possible that any statesman should be found, in this country, ready to sacrifice the rights and interests of the smallest community, for the purpose of flattering such prejudices, and should venture to do so, because the community injured is weak and helpless.

Confident in the justice of our cause, and in the honour as well as justice of his Majesty's Government, I have, &c.

We were one day accosted by a beggar in Guernsey, and as this is by no means a common occurrence in that part of the Queen's dominions, it excited much curiosity. The girl (her age might be fourteen) said her father was ill in bed, and the family had no bread to eat. She gave her name and place of abode. A careful enquiry was instituted, and the following authentic information obtained. The man was in good health, and in full work, and in receipt of 15s a week. The house he lived in, with about two-fifths of an acre of land adjoining, were his own, subject to a mortgage payment of not more than one pound a year. This girl was the only beggar seen or heard of, during a month's sojourn in the Channel Islands.

Religion

The religious aspect of the islands is very like that of Great Britain. The established church is isolated, and strives to be dominant there, as here. The Methodists are very numerous, and to this active body of christians great praise is due for the diffusion of evangelical instruction throughout the islands. There are Independents, Baptists, &c., as in this country. There are a few catholics in Guernsey, who meet in a neat chapel. In Jersey they have lately built a commodious chapel. The population of St. Peter's Port, the only town in Guernsey, is between fourteen and fifteen thousand; the episcopalian places of worship supply 4602 sittings; and the various meeting-houses belonging to other bodies, 5991. In the year 1750, there were no dissenters of any kind on the island.

The conflict with the UK Government in the 1840s: the Napier affair

It remains to give some account of the disputes which have lately agitated the islands, and to which the leading journals of England have frequently referred. Both Jersey and Guernsey have been brought into collision with the Home Government, but from causes totally distinct and unconnected: so that the vindication of Guernsey would leave the dispute of Jersey untouched, and vice versa. The Guernsey controversy has called forth the pamphlet of Mr. Bowditch, which is a document of but little interest, excepting as it has elicited the crushing reply of Mr. Tupper.

The Lieutenant-Governor of Guernsey is Major-General Napier, famous both as a soldier, and an author; but apparently unfitted for civic duties, by his military habits and imperious temper. He has recklessly involved himself in a succession of disputes with the royal court; and his conduct has been petulant, overbearing, and fatuitous. The historian of the Peninsular war has certainly placed himself in a position, in which every one who admires his chivalrous character, and did admire his liberal professions, will grieve to see him.

In the month of June 1843, General Napier, having been informed that a Frenchman named Du Rocher, who had committed bigamy in Jersey, was residing in Guernsey, determined to have him arrested, with the presumed intention of sending him out of the island. Du Rocher concealed himself in the house of a Mr Orchard, a British resident, in whose family he was French preceptor. Mr Orchard had a French servant named Le Conte. The police finding that this servant knew something about Du Rocher, questioned him; but he evaded their enquiries. Du Rocher, soon after, quitted Guernsey. The governor, vexed at his escape, caused Le Conte to be imprisoned, on the charge of 'having annoyed the constable in the execution of his duty;' and the following morning, commanded that he should be expelled from the islands; thus banishing not the master, but the servant, for keeping his master's secret. This act of stern authority in an island where there are hundreds of French residents, occasioned great ferment. The constable having admitted the expulsion, was asked by the royal court, whose subordinate he was, by whose authority he had acted; and he named the governor. The court (i. e. the bailiff and jurats) then sought, according to their right and custom, an explanatory interview with the governor, who appointed the 9th of October as the time, and his private residence as the place; but instead of receiving the court with the respect due to their station, or with the courtesy of a gentleman, he had the chairs removed from the room, except an elevated one for himself, declined to enter into the conference specially provided for by his oath of office, and dismissed the gentlemen who had waited on him in a friendly and conciliatory spirit, with contumely. Out of these proceedings two questions arose—the question of the governor's power of banishment, and the further question of the right of the royal court to decent treatment when they applied for a free and friendly conference.

On the 1st of January 1844, a number of soldiers met, on the public road, an Englishman named Clark, and his wife, and in a violent and cowardly way assaulted them, leaving Clark in such a state that the medical attendant declared, on oath, he could not answer for his life. A constable was sent to the Fort to claim the offenders. Three were recognised, and removed to jail, the name of one being Thomas Fossey. This man was convicted, 'on evidence as conclusive as was ever heard in a court of justice,' of a most cruel, unprovoked, and cowardly assault, and sentenced to two months' imprisonment. The next morning, without making the slightest enquiry of or reference to the crown lawyers, General Napier wrote to Sir James Graham, and obtained a free pardon. Nor was this all. The writ of pardon should have been, according to custom, first conveyed to the court and registered, and then executed through the sheriff. General Napier went himself to the jail, presented the document, and ordered the turnkey to release the prisoner. That officer hesitated, and wished to consult his superior. The general immediately commanded the fort-major to bring down troops and force the jail; to avoid which catastrophe, the turnkey complied with the order. The whole island took the alarm at these unequivocal indications of military despotism. The governor was not a man to halt in his purpose. He bade the law officers prosecute the turnkey on a charge of disobedience. He was tried on the third of March, and unanimously acquitted.

The excitement continued, and was again fanned, when, on the 30th of March, the governor, without provocation, taxed by letter, one of the jurats, Sir William Collings, with having, as a judge on the bench, been guilty towards him, her Majesty's representative, of infamy, falsehood, dishonour, and the breach of his word as a gentleman: which monstrous attack induced Sir William, on the 2nd of April, to appeal to the Lord President of the Privy Council.

These various causes of difference remaining unsettled, on the 20th of May, there arrived her Majesty's steamer Dee, with a Queen's Messenger, and her Majesty's steamer Blazer, with the depot companies of the 23rd, 42nd, and 97th Regiments, from the Isle of Wight. They were followed, on the 21st and 22nd, by other bodies of soldiers. On the 23rd orders were issued that the island militia should not turn out on the 24th, to celebrate the Queen's birth-day, as they had been wont to do.

The landing of the soldiers took the natives by surprise. Every one was at his wits' end to know for what possible purpose they had been sent: some supposed a war was about to break out with France; others, that O'Connell was about to be imprisoned in Castle Cornet, a Guernsey fortress; a few, that General Napier had sent for the troops,—which, however, he denied. The truth soon leaked out: the six hundred soldiers had been despatched to quell a conspiracy against the life of the governor! A conception more absolutely ridiculous was never entertained. That there might be a wicked man, or a few wicked men, in Guernsey, who would be guilty of such a plot,was a possibility none could deny; but that there should be any general conspiracy, requiring a body of troops to put it down, will appear to everyone acquainted with the people, quite incredible. General Napier would not commit a more laughable blunder, if he were to charge such a plot on the 'Maternal Society.' If the natives had been told that they were angels and had wings, or demons and had tails, they could scarcely have been more astounded than when they heard they were conspirators. In due time the whole affair came to trial, and underwent a very searching and lengthened scrutiny; fifteen days being, in whole or in part, devoted to it. The General attended the sittings of the court and frequently questioned the witnesses.

Strange to say, though an army had been sent for the governor's defence, the persons accused were only five. Two of these five had sought, some months before, to resign their commissions in the militia, on the ground of some dissatisfaction with the promotion of another officer. The General would not allow them to resign. A friend interposed: the affair was settled amicably: the letters on the subject were burnt, the General himself having given them up for that purpose, 'and with the understanding and promise that there should be no further question of their contents.'¹ Will it be credited that copies of these letters were produced on the trial? We do not profess to be very conversant with the soldier's code of honour, but should have expected that the author of the History of the Peninsular War would rather have been shot than allow these copies of letters to see the light, especially as they were in no way connected with the alleged conspiracy.

Of the five accused persons two were set at liberty, after an examination answering to that of a grand jury in England. The remaining three were brought to trial. The witnesses were in number eight, but three of them only gave testimony bearing on any of the accused. These were the Rev. Daniel Dobrée [Dobree], and Mr and Mrs Waterman. Of these three, the first made himself notorious a few months ago by a letter in the 'Times,' the object of which was to prove himself of sound mind: of which sanity he gave rather strange evidence on the 13th of March. The parishioners being assembled on that day for a public purpose in the churchyard, the reverend gentleman took up his post in the church, fastened the windows with nails and gimblets, placed the union-jack over the pulpit, clothed himself in a surplice, and in that array stood at one of the windows making grimaces at his assembled neighbours.² As to his testimony on the trial, it is sufficient to say, that the counsel for the prosecution abandoned it as worthless.³ J Waterman and his wife deposed that two of the accused had talked in their shop about shooting General Napier, and that they had done this in the presence and hearing of a man of the name of Smith; who being called, declared he had never heard any such words, either there or anywhere else.

A more disgraceful cause never came before a court of justice. The whole affair is a romance, and nothing is wanting to make it complete but the production of the correspondence between General Napier and Sir James Graham, for which we trust some member will move in the present session of parliament. [¹ Authentic Report, p. 61. ² Authentic Report, pp. 40,43. ³ Ibid, p. 77.]

The various items which have been explained make up the case at issue between General Napier and the people of Guernsey. That case has been heard before the Privy Council. Notwithstanding the efforts made to repress enquiry by technical objections, the decision is, on the whole, favourable to the people.*

[*In taking leave of Guernsey, we may mention the possible existence of a document which might, just now, be of no small interest, could it be discovered. The following is from Bridges's History of Northamptonshire, published in 1791:—'In the library at Kirby, the seat of Lord Hatton, is a MS account of the island Guernsey, written by the first Lord Hatton, said to be admirably well done, and ready for the press.'—vol ii. p. 315. The first Lord Hatton died in 1670. We have made inquiry after this MS, but without success.]

Jersey

The Jersey cause is still undecided; and grievous is it to observe the ignorance and prejudice with which it has been discussed in the public journals of this country. We have no love for Jersey: it is plagued by party spirit to an extent of which, even in England, we can hardly form a conception; the moral tone of the island is far lower than in Guernsey, and it lacks the exquisite cottage-homes of the sister island. Yet there are signs of improvement, among which may be mentioned the establishment, on the 3rd of January last, of a new English newspaper, free from the low-lived asperities which have been an utter disgrace to the community tolerating them.

In May last an Englishman, Mr Charles Carus Wilson, published an insulting letter to the lieutenant-governor of Jersey, Major-General Sir Edward Gibbs. A public meeting of the native and English inhabitants of St. Helier's was convened to express indignation at this wanton attack. The chief magistrate of the town, Mr. Le Sueur, presided. Mr. Wilson sent a written apology to the government-house, and then published a libel on Mr. Le Sueur, who brought an action against him. On the trial, Wilson insulted and bullied the court; he shook his fist at the judges, brandished a brandy bottle, poured out a glass and tossed it off with an insulting gesture to the bench, told the court it was corrupt, boasted that he would galvanize the judges, &c. After long forbearance, he was sentenced to pay a fine often pounds to the Queen, and to apologize to the bench. He refused to do either, and was imprisoned. In prison his treatment has been as lenient as possible. He has applied in England for a writ of Habeas Corpus, which would remove the cause to Westminster. The writ has been granted. It it legal? That is the sole question at issue; and it will soon be decided before the proper tribunal. All the eloquence, therefore, of the newspapers about 'a monstrous anomaly,' and 'the sovereignty of the Queen,' &c., is mere waste of words.

Habeas Corpus affair

In order that an act of the imperial parliament may become law in the Channel Islands, two things are said to be requisite: the islands must be named in the act, and the act must be registered in the islands, having been transmitted for that purpose by the Privy Council. The Habeas Corpus Act has the first of these requisites, but lacks the second. Nor could it be made to run into those parts of the Queen's possessions, without infringing the constitution there enjoyed. Its effect, moreover, would be to render justice complicated, expensive, and tardy. The right of the inhabitants to be tried in their own local courts is 'one of their most ancient and vital privileges.'*

In the year 1831 some paupers—children of soldiers—were sent to Guernsey, from St. Pancras, London. The island authorities denied that the paupers were chargeable on the island, and refused to allow Capes, the beadle of St. Pancras, to leave without them. Some months after, Capes and the paupers being still on the island, the parish of St. Pancras obtained from Lord Tenterden a writ of Habeas Corpus for the beadle. When his lordship's tipstaff appeared in Guernsey, the Royal Court immediately refused to make any return to the writ. Lord Tenterden then issued a warrant for the apprehension of the deputy sheriff, by whom Capes was detained. The tipstaff, who served this warrant on the 7th of May, was himself forthwith given into custody, taken before the court, and told that he had no authority in Guernsey. The Government now interfered, and an order of the Privy Council was sent, bearing date June 11, 1832, requiring the Habeas Corpus Act to be registered in the islands. The authorities in both Jersey and Guernsey, resolved to suspend such registry till they had remonstrated. Deputies repaired to London, Mr. Brock being one. The Order in Council was abandoned, the act was not registered, the beadle and paupers returned to London.

The institutions of the Channel Islands are not indeed perfect, but they are such as the people venerate for their antiquity and love for their fruits. Why should they be deprived of them? We trust that the good sense of the British public will prevent such a catastrophe. Let the institutions in question be amended where they need reform; but let them not be dealt with in ignorance or prejudice.

[* The Jersey authorities have admitted the jurisdiction of the Court of Queen's Bench. They should have declined it, and the whole case would then have been argued before the Privy Council.]