On board the Tulloch Castle to Melbourne, 1852

27th July 2015

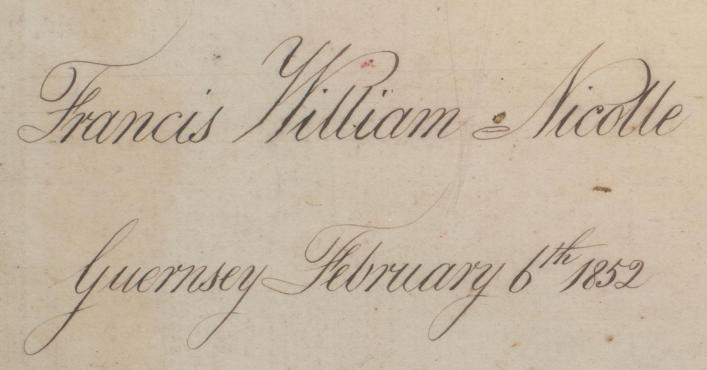

The 1850s gold rush in Australia attracted thousand of immigrants and would-be prospectors, and Guernsey was by no means immune to gold fever. 18-year old William Francis Nicolle recorded his voyage to Melbourne in the summer of 1852 in his Journal, which was generously donated to the Library by Stephen Foote. Nicolle followed this with an account of his return from Australia in the freezing cold on board the Avon. His Journal also includes a substantial amount of family history material (Nicolle, De Garis, Lainé, Lamble &c.), as well as other accounts of later voyages made on board cargo ships. He was a carpenter by trade, and the book also includes carefully written instructions for calculations, presumably for reference purposes. Finally, his poem in memory of Nicholas de Mouilpied, who died on the voyage out, aged 22.

Written on board the ship Tulloch Castle, on her voyage [from London] to Melbourne, Australia. 350 passengers. 126 days. 1852.

I left Guernsey in the 23rd July at 20 minutes before 10 o'clock ....

[....]

The Cape of Good Hope

10th [October.] Fine weather, contrary wind light, at 9 o'clock this evening one of the passengers was drunk and insulting everybody, the Captain [Murray] gave orders to lash him to the stanchion till he made up his mind to go to bed quietly. The wind is now light and fair, heavy sea.

11th. Fine dry weather, very heavy sea, wind light. At 10 o'clock a fine breeze sprang up, this afternoon we set our stunsails in, about two hours after we were double reef topsails, very heavy weather, about midnight our spanker got foul of the wheel chains, it was soon cut adrift.

12th. Blowing hard heavy sea raining very hard at 8 o'clock, rough night.

13th. Sea mountains high this morning, between 3 and 4 o'clock a sea knocked the ships galley all over the decks in ever so many pieces, the keel of our long board was broken by an anchor rolling against it, we had a narrow escape of losing the boat, it was not far from gone, the boxes in the hold were all capsized this evening. Between four and five o'clock as the second mate Mr Godfrey was in the act of tying a knot over the starboard side of the ship, his foot slipped and he fell overboard. The life Buoy was thrown over the Poop but it drifted in a contrary direction, the life Boat was lower'd with five brave men in her, the sea was very rough and blowing hard, we canted the yards and put the ship about with her fore topsail backed and her mizen sheet set so as to steady the ship. The boat was no sooner lowered than she was out of sight (we sometimes just caught a glimpse of her now and then as she rose on the top of the waves until at last she got out of sight), she had now been out about two hours, we had given them up, we hoisted a red flag and a signal light on her mizen peak as a signal for the boat to return as there was every appearance of a very rough night and getting dark, the sky very black, the sea roaring and beating against the ship. I happened to be on the top gallant forecastle when all at one I saw the little boat about thirty yards off on the starboard bow, she crossed our bow and got on the larboard side, she could not get alongside for some time, the sea being so high. At last she got alongside. A rope was thrown from the poop to the boat and they caught it. We hauled her up and the five men in her, they had seen nothing of poor Godfrey. As he fell he swam so as to get in the ships wake, we could see the Albatrosses around him, but a wave carried him away. It was about seven o'clock when the boat returned. Every thing was done for him that could be done (at the time he fell overboard we were going at the rate of 9 miles per hour). We now set sail and went on our course and at eight o'clock we experienced a dreadful hail-storm, the hail fell like bricks, thundering and lightning blowing very hard. We had a dreadful night of it under double reefed topsails off the Cape of Good Hope.

Thursday October 14th. Today Mr H Maillard is appointed to take place of Second Mate. An Albatross caught which measured six feet three inches.

15th. Under reefed topsails in a gale of wind.

16th. Under reefed topsails in a gale of wind.

19th. Do. Do. in a gale of wind.

Wednesday 20th. Off the Cape of Good Hope fair wind light light stunsails set, fine cold weather this evening. I went on deck as usual about seven o'clock. I went below at eight, had a chat with Mr Dale with N Le Messurier alongside, when at 9 o'clock we heard a cry, a man over board. The weather being so fine the Captain could not believe it so we were all sent below in our Cabins and the sailors sent down to see if it was any of the passengers. They were all found, but when it came to No 42 they found it was poor Nicholas de Mouilpied. How he fell is not known. At the time we were sailing about 5 knots per hour in a smooth sea. The Life Boat was put out with a compass and five men. He must have soon gone down, they could see nothing of him. At noon we were in latitude 40 deg. 3 ms, Longitude 18 degrees 18 mins 15 sec East. I saw him walking on deck at a ¼ past seven the same evening, the last time I saw him.

Lines written on the death of Mr N de Mouilpied, who fell from on board the Tulloch Castle whilst on her voyage to Port Philip and was drowned on the night of the 20th of October 1852 in latitude 43 degrees 3 min South, Longitude 18 degrees 19 min 15 sec. East.

The wind blew fair, all hoped it might last

We had forgotten our loss, though a week scarce had past

Since Godfrey fell over, the Ship's Second Mate

The night had commenced, the Bells struck eight

All was quiet below, on deck the band played

Some were dancing so happy, each heart light and gay

On the Poop was the Captain and mates all alone

A sound came form the water, twas a low dying groan

They rushed to the side, by the three it was heard

The Captain shouts aloud, There's a man overboard

We all rushed below, not a moment to wait

A young man was missing, a friend of the Mates

The ships course was stopped, the boat was soon manned

By five of the Crew, 'twas a bold gallant band

We watched the Life Boat, the moon it shone bright

As she shot o'er the waves and was soon lost to sight

The Captain paced to and fro, and showed by his glance

For the life of our messmate there wasn't a chance

For the water was cold, he could not swim long

In the wake of the vessel he'd be carried down

The boat then returned after some miles they had been

No voice had they heard, not a thing had they seen

Men thought different things and from what part he fell

No human eye saw him, no tongue could then tell

Our sails were soon set and the spot lost to sight

But we ne'er can forget the sad tale of that night

A solemn stillness prevailed amongst the bold crew

They worked all in silence, in whispers so low

And the Mate his companion, tho' not oft alarmed

At the sea in its fury or the wilds of the storm

Was not quite unnerved, though he did not despair

He had a safe refuge, his trust was in prayer

But he knew his friend's parents were anxious to hear

And then what sad tidings his letter must bear

The loss of their son of whom they were proud

The deep sea was his grave, the sea weeds his shroud

In the deep waste of water he sank all alone

No bell tolled his knell, he had no Gravestone

But we trust they might meet him on that happy shore

Where troubles all end, and we part then no more.

See also Off to Australia, 1854. David Kreckeler's book, Guernsey Emigrants to Australia, Guernsey: 1996, gives a good deal of information about these men. Nicolle was from St Peter Port, son of Thomas Peter Nicolle and Elizabeth Lamble. He later sent a letter back from the gold diggings, which he wrote in February 1853 and which was published in the Comet as 'Chips from the Diggins,' July 7 1853; he mentions his friend Henry Maillard, John Potter of Vauvert and a sail-maker named Robilliard. Along with Nicolle's letter is a report of the death at the diggings of Jean de Jersey of Mon Plaisir. A married man of around 26 with a very young child, he was trying his luck in Australia with his two brothers, who had joined him from South Africa. Nicholas de Mouilpied was also a St Peter Port man, and a carpenter. He was the son of Nicholas de Mouilpied and Susanne Vidamour. [Many thanks to David Kreckeler for this information.]

For a similar diary, see J A Lainé, Quarterly Rev. Soc. Guern., VI (4) Winter 1950, 'Voyage to New Zealand in 1851.' The diary of Juliana Lainé, wife of Thomas L Lainé, of Canterbury Villa, Rohais; she was 22 years old when she left Guernsey (although she eventually returned), and her voyage out was on the Labuan.