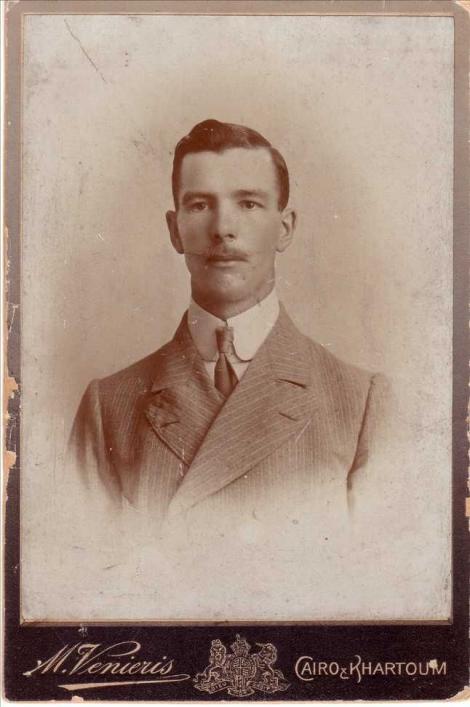

Bimbashi Garland

Major Herbert Garland (1880-1921) was an explosives expert and the author of a short romantic novel set in Guernsey entitled Diverse Affections; his life is much more interesting than his novel. The effects of the devastating techniques he pioneered in Arabia are still being felt today.

In 1906 Diverse Affections* was published by The Century Press, in London. It was advertised in the Guernsey Evening Press; the Press themselves took out advertising in the novel. The story is set in Guernsey and the author was a 26-year-old member of the Army Ordnance Corps stationed in the island, named Herbert Garland. Unfortunately the novel, a somewhat arch and possibly semi-autobiographical love story, can best be described as slight and received a lambasting from the Guernsey Evening Press’ own reviewer in October of 1906. It contains, however, some charming descriptions of Guernsey—'a glittering pearl in the cerulean waters of the Channel'—and comments and asides on the social life of the island, although the young author is at pains to stress that it could have been set in any seaside resort.

The historic church of St Peter’s is noticeable in the foreground with its square tower, while the spires of other places of worship raise their symmetrical contours at intervals above the tree-tops. On the right, as one looks ashore, the country is flat, and the busy little village of Saint Sampson’s, with its quaint, whitewashed cottages and its numerous windmills, reminds one of the Dutch coast. Even from this distance Guernsey seems perfectly tranquil and happy; and it is indeed.

No filthy black smoke is seen curling its way aloft to putrefy the atmosphere; no tall chimneys exhibit their ugly profile on the horizon, or appear in silhouette against the landscape; no clangorous motor-omnibuses emit their nauseous odours in the thoroughfares. All is calm, and clear, and clean. The only rattle which may be heard is that of the many carts and drays dashing down to the wharf with their loads of fragrant flowers and fruit, to be despatched from here to all parts of Great Britain. Heaps of boxes lay alongside, awaiting shipment, giving off delicious perfumes, and causing the tourist, as he surveys the scene, to wish that he might live permanently amongst such charming surroundings, instead of only temporarily (p. 9).

Herbert Garland’s novel-writing skills are not what makes him interesting, however. By the time Diverse Affections was published he had been transferred to Khartoum, having spent four years in Guernsey. His grandson contacted the Library with information about his life.

'Judging by the book he clearly loved his time in Guernsey. The name he used for his principal character Stevenson (Lawson) was his mother’s maiden name (and also my mother’s middle name). He had quite a life; after several years in the Sudan he transferred to Cairo and became the Superintendent of the Explosives Laboratory and Magazines' (Chris Mitchell.)

The first year of the war he invented, and superintended, the manufacture of the 'Garland' grenade, sending 174,000 to the Dardanelles and Gallipoli.

A man named Garland from the Cairo arsenal made improvised bombs from food tins filled with bits of barbed wire and spent Turkish bullets, gunpowder or some kind of explosive detonator, and a fuse wire. One man held the bomb behind his back with a match-head on the fuse, and a second man rubbed a match-box against the match-head to ignite the fuse, shouted 'Ready' and the first man threw the bomb. These homemade devices were unreliable and dangerous, but were the only substitute for grenades until late May 1915.¹

In October, 1916, he left Cairo for Arabia, where he trekked in the Hejaz desert disguised as an Arab. An Arabic speaker, he taught the Arabs the use of explosives and later led expeditions to mine the Hejaz Railway, along with T E Lawrence, who made use of the 'Garland grenade.' Garland was the first to destroy a Turkish train. By then a Major, Garland and other officers² went on to bomb the railway repeatedly, but Lawrence seems to have ended up with the credit for it.³

Garland, attached to the Egyptian army, was military advisor to the sharifian armies, at a time when the British also gave financial support to the Bedouin tribes fighting against the Turks, and was known as Bimbashi (or Major). He knew Lawrence well, and reported that Lawrence was the only Westerner able to 'submerge his identity'4 and to see the Arabs as they saw themselves; Garland himself had little time for the undisciplined Bedouin armies of the Sharif, and disapproved of the huge amounts of money that went via Lawrence to fund them. Lawrence mentions Garland in his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom and was generally complementary about him:

Garland takes over my cipher. He is a most excellent man and has won over everybody here. The very man for the place.5Garland was an enquirer in physics, and had years of practical knowledge of explosives. He had his own devices for mining trains and felling telegraphs and cutting metals, and his knowledge of Arabic and freedom from the theories of the ordinary sapper-school enabled him to teach the art of demolition to unlettered Bedouin in a quick and ready way. His pupils admired a man who was never at a loss. Incidentally he taught me to be familiar with high explosive. Sappers handled it like a sacrament, but Garland would shovel a handful of detonators into his pocket, with a string of primers, fuse, and fusees, and jump gaily on his camel for a week's ride to the Hejaz Railway. His health was poor and the climate made him regularly ill. A weak heart troubled him after any strenuous effort or crisis; but he treated these troubles as freely as he had detonators, and persisted till he had derailed the first train and broken the first culvert in Arabia. Shortly afterwards he died. (From Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Cambridge University Press, 1935, pp. 114-5, a first edition in the Library).

Garland's critical attitude towards the Arabs, however, and perhaps his poor health, led to his being withdrawn from the region. He supervised the surrender of Medina, and after the Armistice his experience of dealing with the Arabs led to his being posted to the Arab Bureau, of which he eventually became Director and Editor of the Arab Bulletin, including in this some of his own experiences. At the same time he was also Superintendent of Laboratories at the Citadel in Cairo, where he had had since before the War chance to develop his personal interest in metallurgy with the study of Ancient Egyptian artefacts and bronzes, producing three academic articles on the subject before his sudden early death in 1921 at the age of only 40. He had been sent back to England following recurring bouts of dysentery picked up in the desert campaigns, and is buried in Gravesend.6

A posthumous work entitled Ancient Egyptian Metallurgy was written from his notes by a Professor Bannister of Liverpool University. It is regarded as an important book but seems to have suffered from poor editing.

Bimbashi Garland’s diplomatic and explosives work is examined in many modern books and academic works covering the period. He was awarded the OBE, Military Cross, the Arabian order 'El Nahdeh,' and twice the 'Order of the Nile,' and was mentioned in despatches several times.

The techniques pioneered by Herbert Garland and utilized to such great effect by T.E. Lawrence now have perhaps more resonance than ever. Here are the closing words of a lecture given by the United States Training Mission in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

The lecture concludes with valuable lessons for advisors in Arab countries today who still contend with the legacies of Arab culture that challenge the implanting of western concepts and strategy in military organizations operating under different principles. The British advisors adapted their own method of warfare to the Arabs as much as the Arabs adapted the use of British explosives and artillery to their raiding culture. Ironically, the use of this fluid means of attack with improvised explosive devices, keeping the initiative with constant surprises, and forcing the enemy who finds it necessary to either remain in fixed positions or move along confined and predictable routes from location to location reminds us of the use of such IEDs by insurgent Arab forces to inflict casualties on US forces in occupied Iraq.

Such is the rather poignant legacy of the gallant author of Diverse Affections, who did not live long enough to leave us his own version of these momentous events.

UPDATE: Since we compiled this article in May 2010, Herbert Garland's contributions and legacy have been recognised by the Royal Chemical Society.

*Although strictly speaking a medical term, the title of the book may come from Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy, which became extremely popular in the 19th century (it was Keats' favourite book). Burton refers to the 'diverse affections of lovers,' using it in both senses as Garland seems to have. The Library has an 1826 copy of this important book which belonged to Osmond Priaulx.

¹ http://history.sandiego.edu/gen/ww1/gallipoli.html

² Falls, Capt. Cyril, History of the Great War, Military Operations: Egypt and Palestine, From June 1917 to the End of the War, Part II, p.399: HMSO, 1930 'Raids on the railway were continued under the leadership of Major H Garland and other British officers.' Available in the Library.

³ http://www.saudibritishsociety.org.uk/main/prev-lectures-7.htm

4 Friedman, Isaiah, British Pan-Arab Policy, 1915-1922, Transaction Publishers, 2009, p. 171.

5 Lawrence, T E, Brown, Malcolm, The letters of T E Lawrence: Oxford, Oxford Paperbacks, 1991.

6 More photographs of him.For books about this period and campaign see, for example: Karsh, E, and Karsh, I, Empires of the Sand: The Struggle for Mastery in the Middle East, 1789-1923: Harvard Uni Press, 2001; Friedman, Isaiah, British Pan-Arab Policy, 1915-1922, Transaction Publishers, 2009; Nicholson, James, The Hejaz Railway; the Arab Bulletin of the period, and works on Lawrence amongst many others.