Fountain Street celebrates the peace of 1763

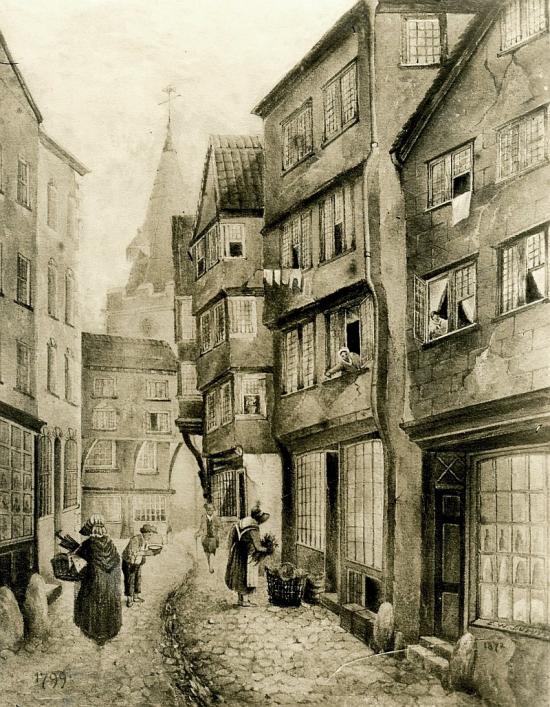

Fountain Street is decorated for a celebration in unusual style; by George Métivier, writing in the Elizabeth College Magazine of 1842. The illustration is of a painting depicting a view looking towards Fountain Street and the Town Church in 1799, the notoriously narrow part being at the end.

For more on the history of Fountain Street see the Lamentations de Damaris.

It was on the Easter Monday of 1763, when peace was proclaimed with France,1 that the mother of my grandmother left her house, which was next door but one to the Cousines Rivouères2 (the Sarnian drug, spice, chintz, and china shop), with une gâche à corinthe which was to be in the fouar (communal oven) before six o’clock, as it was intended for a breakfast in honour of the happy event. The bells were ringing; and all the town, in other words, all the houses one hundred yards round the Church, for such was St Peter Port at the time we are speaking of, were en émeute; and the soldiers in full uniform, I mean full dress, were assembling in the Market-Place. When she entered the fouar, whom should she find there but Esthar Neho, Aune Clink, L’szabo Sandre, and two or three others of her acquaintance. The conversation naturally turned on the war, its dreadful consequences, and the peace which had just been concluded. Divers as well as numberless were the sentiments expressed on the occasion, but all were joined in deciding that the street must be decorated, to show the feeling which pervaded the whole community; and being unique as to the style of its buildings and the nature of its inhabitants, it was but fair that it should also be distinguished by the superior splendour of its decorations.

As soon as the gâches were put au fouar, and whilst they were being baked, each hastened home to make the necessary preparations, and in less than half an hour might be seen floating in glorious majesty a red silken petticoat and a blue cloth pair of sailor’s trowsers suspended from a superannuated broomstick, which was supported on two opposite window casements across the street. A little farther down hung a similar insignia, except that in this case it was an elegant yellow silk cotillon piqui (petticoat); and from the upper story of every third house were suspended crown and garlands of flowers, whose resplendent verdure was relieved by numerous silver goblets, coffee and tea-pots, not to mention a vast concourse of soup spoons and ladles, and a multitude of tea-spoons of a similar metal, which jingled most harmoniously in the gentle breeze; and which, together with the merry hum of voices underneath, formed a tout-ensemble at once agreeable to the eyes and the ears. The shops assumed a gayer appearance than usual; Esthar Neho’s, for instance, displayed an astonishing variety of nuts, almonds, penny whistles, and purple-dyed eggs, all at uncommonly low prices. The apothecary’s shop was also ornamented in the most approved style, with red and yellow silk handkerchiefs, supported by huge chests of tea, and these were most invitingly set with real china tea-cups and saucers, which were in their turn supported by diminutive vases containing rhubarb, a few ounces of salts, bâsli, manna, and the all-efficient medicine yclept senna; all were arranged in a 'light fantastic order,' most happily blending together the utile dulci. The Misses Rivouères themselves, the fair owners and dispensers of these useful articles, by their holiday attire, their manchettes à trais rangs and their neat couaiffes à but, seemed to invite purchasers. Such was the appearance of the street on the morning of this joyous day; but a far more exciting scene was reserved for the afternoon; the military had returned home; had cleansed their fire-locks against the next 'turn-out,' and had just finished their dinner, when a hogshead of wine was rolled near the Church; the top was knocked off, and two men on stools, with jugs in their hands, were distributing the wine to a century of women, who had congregated round with cans, soup-plates, and other vessels capable of containing liquids. Nor was this all; a heifer, covered with garlands, had paraded the town during the morning; and now, spitted on a huge elm, was being roasted whole on the New Ground, to the ineffable delight of a somewhat numberless concourse of people who, as many as could conveniently approach, assisted at his obsequies. The last merry peal was ringing in St Peter’s Tower, and all the matrons of Fountain-Street and the environs were hastening to pass the evening at the veille—and thus ended a holiday in Guernsey fifty years ago.

Si j’si l’ar triste, et la mine un p’tit pâle,

Au temps passai, si faut que j’dise adi,

Messiûs, mesdames, je n’serrais que j’n’en pâle,

Et d’temps en temps je rentre en paradis.

From the Elizabeth College Magazine, 2 (I), June 1842, pp. 25-8.

1 The Treaty of Paris, which ended the 7 Years' War, was signed in February of 1763. Easter Monday fell on April 4th in that year. The London Chronicle for 1763 reports the festivities thus:

Island of Guernsey, April 5. Yesterday peace was proclaimed here, at the usual places, with much solemnity. The guns of the Castle were fired, and answered by volleys from the Regulars and militia, drawn out on purpose, and by the guns of the nearest batteries, which gave three rounds. Mr Abburow (who had acquired an immense fortune during the war) gave the Populace a fine ox, which was roasted whole; likewise the Merchants and other gentlemen provided a great quantity of bread and wine. The evening was concluded with bonfires, illuminations, ringing of bells, and with the most publick demonstrations of joy possible.

Thomas Abburow (1723-1771), from Fareham, is recorded in the Register of Duties paid for Apprentices' Indentures in 1752, as a master butcher in Guernsey.

2 The Misses Rivoire.